[ad_1]

Supply of Life by Toni Huber

In a breathtakingly vast canvas full of numerous analytical drilling down, japanese Bhutan is lit up intimately for the primary time in Huber’s Supply of Life.

To be exact his topic is non-Tshangla talking a part of japanese Bhutan consisting of areas the place Dzalakha (associated to Brag-gsum language spoken by mkhar builders of Tibet), Kurtoedpaikha, Dakpakha, Khengkha, Bumthangkha and Chocha-ngacha (Tsamangkha) are spoken. Sources of previous festivals, cultures, languages, folks etymologies, mkhar- structure, in-migration, and settlements amongst these East Bodish linguistic audio system of japanese Bhutan have been largely unknown till Huber’s monumental analysis lasting 15 years.

Title: Supply of Life

Writer: Toni Huber

Vol I – 640 pages

Vol II – 499 pages

He takes us on an enriching journey of study of historical Tibetan texts in addition to of historical texts in Kurtoepaikha, Dzalakha, Dakpakha, and Bumthangkha. Handwritten folio manuscripts of those Bhutanese dialects present shocking proof of our ancestors writing their dialect lots of of years in the past. This course needs to be renewed if these languages are to be revitalized and the sensibilities of their cultures maintained.

In the middle of his work, Huber translated over 1,000 pages of some 100 manuscripts he got here throughout. Huber’s multi-disciplinary and cross-boundary method takes us into East Bodish languages by means of which shared lexicons and ideas have percolated, and over huge geographical expanses from Zhemgang in Bhutan, Subansiri river valleys stretching from Arunachal Pradesh into Tibet, and additional east to Yunnan and Sichuan the place Naxi and Namuyi individuals stay.

He deepens our understanding in radically new methods in regards to the non-Buddhist cosmology; performances, gesticulations and ritualized bodily actions; verse chants about journey of gods and verse chants accompanying dances; materials tradition and equipment of rituals; devices and objects; natural world, together with bat, associated to the cult; meals and vitality substances; and the position of key ritual performers.

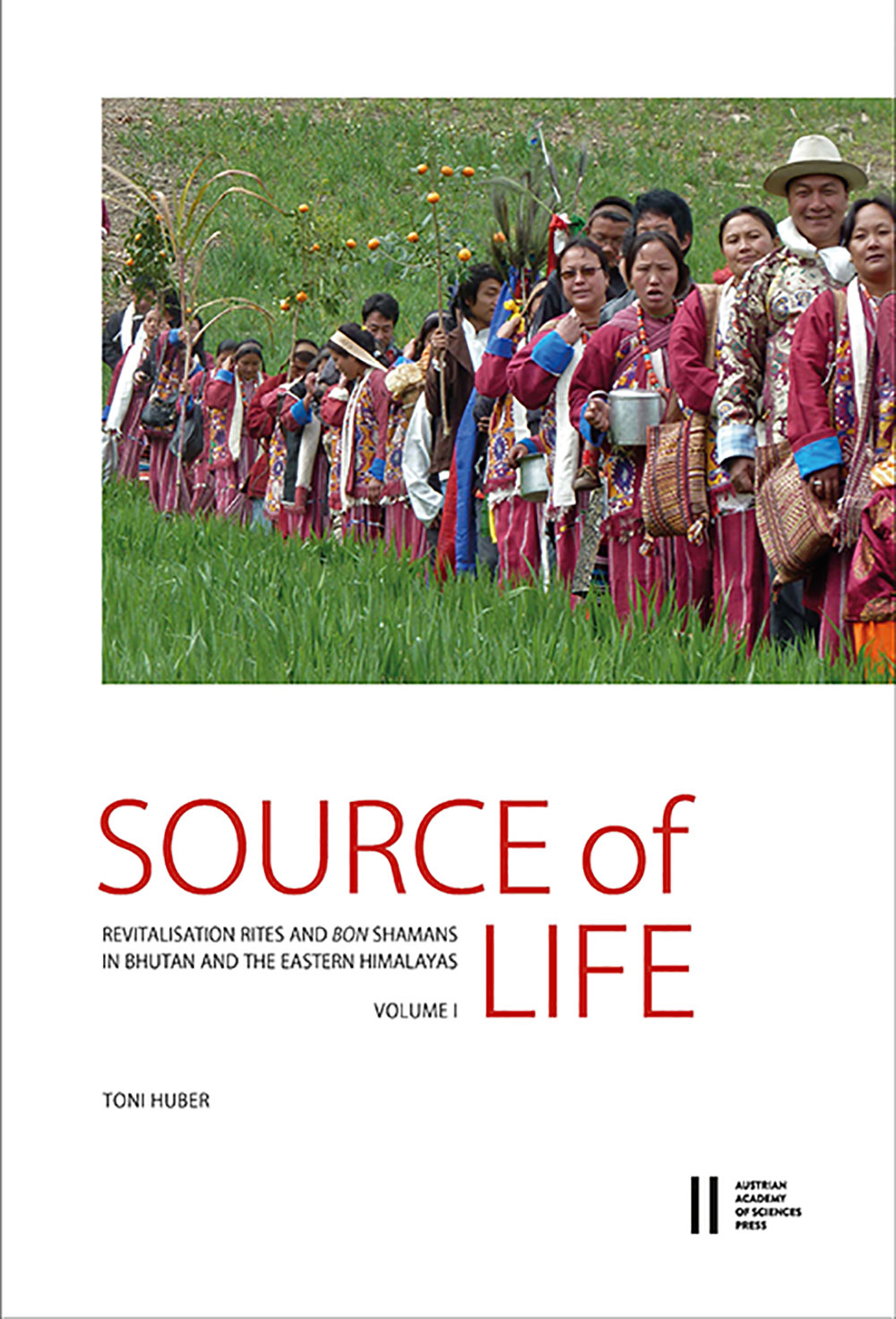

Tsango competition in Khoma

The important thing ritual specialists are recognized variously as rup, phajo, kharipa, mi sim, shu’d, gongma, ga-sdang, nami, habon and bonpo relying on location. The strategies of rites embody chants, dances, divinations, omens, and prognostications of future; and goals of the important thing ritual performer similar to goals of gods for the reason that key ritualists are referred to as lha mi or lha’i mi. His work challenges and shifts our hitherto imprecise and inaccurate views about japanese Bhutan. Huber’s work mustn’t solely adorn the cabinets of directors, lecturers, and planners, however they need to be actively referred to stop accelerating decline of historical japanese Bhutanese traditions.

After years of finding out Arunachal communities, Huber visited his analysis space in Bhutan – Tongsa, Bumthang, Zhemgang, Mongar, Kurtoed, Tashi Yangtse and Tashigang – many instances between 2009 and 2014 on the invitation of the Centre for Bhutan Research. The Centre was eager to assist such a number one ethnographer additionally to mark the start of the reign of His Revered Majesty who has hooked up nice significance to understanding our nation in all features. The result’s astonishingly unique. The primary quantity of Supply of Life has 640 pages, and the second quantity has 499 pages. Its richness and depth have made the ebook an epic of Himalayan ethnography. Guntram Hazod (2020) acclaimed it in his assessment as a typical within the area of Tibetan research and Himalayan ethnography, a category by itself.

Huber’s earlier works resembling The Cult of Pure Crystal Mountain (1999) about Vajra Varahi’s Tsari Ney and The Holy Land Reborn (2008) demonstrated extraordinary scholarship capable of illuminate the usually convoluted and sophisticated method by which the pilgrimage hotspots have developed over millennia and disappeared and acquired acknowledged and reappeared elsewhere.

Supply of Life maps japanese Bhutan together with contiguous areas of Dirang and West Kameng in Arunachal Pradesh the place the worship of Srid-pa’i lha (lha of procreation or the lha of phenonmenal world, as he calls them) has unfold, throughout ethnic and East Bodish linguistic teams. But Huber clarifies that it’s distinctive to this space, as at current Srid-pa’i lha worship is confined solely to those transborder communities. Although it may be traced again to Lhobrag, none of it exists in Tibet suggesting that it might need been assailed by different spiritual sects or political forces. Sure features of the cult are prevalent among the many Naxi of north-west Yunnan and western Sichuan, some 800-1000 km additional east alongside the identical geographical stretch. Vol 2 is a rigorous exposition of his new speculation that Naxi and Qiang individuals and the Srid-pa’i lha communities of japanese Bhutan have a shared ancestry, drawing on linguistic cognates and similarities of rites and beliefs.

One of many important distinctions between Srid-pa’i lha cult on the one hand and Buddhism or Yungdrung Bon on the opposite is that Srid-pa’i lha cult believes in bla (pla in Dakpakha, pra in Dzalakha, cha in Kurtoedpaikha) as a divisible and a number of vitality precept versus unitary and singular precept in Buddhism. He distinguishes Srid-pa’i lha cult as a social and cultural phenomenon. He considers it not spiritual, in distinction to Buddhism or Yungdrung Bon. However there is no such thing as a worth judgement supposed in distinguishing it as non-religious. Labelling it as non-religious doesn’t imply that it’s inferior. Lamas and officers and equally inclined individuals are liable to be dismissive about Srid-pa’i lha cult. In reality, this perspective can and has led to discouraging the tradition that sustains the communities. A better and extra versatile capability of the Srid-pa’i lha worshipping communities is that they’re multi-polar, being Buddhists in addition to honouring Srid-pa’i lha deities and native numina. There isn’t any good purpose why they or others can not have such a number of identities.

In quantity 2, Huber disambiguates additional the complicated and deep cosmology of Srid-pa’i lha cult which differs from Buddhism and Yungdrung Bon. In doing so, three essential ritual texts for his evaluation are the rnel dri ‘dul ba manuscript, and ste’u and sha slungs manuscripts. Huber notes a major level that phrase bon doesn’t happen in any of those manuscripts although gshen does a couple of instances. All three of those illustrated texts are dated to the eleventh century and all three originated in Lhobrag in Tibet, fairly near north-eastern Bhutan. These three historical texts articulated cosmological ideas and mundane rites from an precedent days. Huber characterizes Srid-pa’i lha cult as a continuity and transformation of concepts and rites present in these key manuscripts.

Central to the cosmology of Srid-pa’i lha is the notion of 13 ranges of vertical cosmic axis delineated intimately within the three historical texts. Sky is the best stage within the axis the place the lha dwell and terrestrial or earth floor is on the lowest stage. Not like in classical Tibetan or Yungdrung Bon traditions, there is no such thing as a decrease subterranean stage beneath terrestrial stage. Within the cosmology of Srid-pa’i lha, life and vitality move up and down between the best lha stage and our personal world. Nevertheless, in its cosmology, there are additionally a variety of different unfavourable and optimistic spirits at numerous different ranges resembling sman, mtshun, bdud, gyen, rmu, srin and many others. There may be additionally wildlife, particularly herbivores on the terrestrial stage. Rites preserve the connection amongst these multitude of beings. The cult’s rites are directed to holding the wilderness plentiful to assist the beginning of lha as human beings.

Srid-pa’i lha worship, significantly lha Guse Langling, was first talked about briefly, within the 1688 ebook by historian-monk Ngawang of Tashigang in reference to the family tree of Dung households. Huber asks readers to transcend Ngawang’s Rgyalrigs because of its limitations. Ngawang paid consideration to identities of Buddhist clans of Jobo and Zhelngo. Nevertheless, Ngawang glossed over Srid-pa’i lha communities of Khu, Seru, gNamsa, Mi, Shar, Ba and Na who’re nonetheless discovered within the area and who’re talked about within the native manuscript Lha’i gsung rabs he got here throughout in Khoma. Huber charts the distribution and historical origin of those clans.

Srid-pa’i lha cult displays pursuit of fertility, copy and virility of human beings and their key livestock resembling sheep, yaks, and horses. These have been well-liked home animals that have been dominant within the surroundings of southern Tibetan Plateau the place the cult rose. Thus, a competition or a ceremony seeks to domesticate tshe (patrilineal fertility), yang (quintessential feminine reproductive efficiency) and phya (sky beings) for the worshiping communities, identical to tshe-khug yang-khug cha-khug of Vajrayana rites which had maybe assimilated this ritual approach. Srid-pa’i lha cult can also be distinctive from Buddhism and Yungdrung Bon as a result of it claims the existence of assorted Srid-pa’I lha, the human progenitor, who stay within the sky and who’s on the centre of its cosmology. Worshipping communities declare frequent descent from their progenitor-lha, whether or not they’re its chief lha, O-de Gungyal, or his divine son Guruzhe, or different lha. Gurzhe, Guse Langling and lots of different variations discuss with the identical lha, Gurzhe, Huber finds. O-de Gungyal and different lha are white, dressed white and experience white horses. They don’t bear any arms not like Vajrayana protector deities. In Kurtoed, an array of siblings (about eight) of Gurzhe resembling Namdorzhe, Yang chung and Yum sum is worshipped, and a few of them are represented in visible arts photographed by Huber.

Gods of Srid-pa’i lha cult descend from the sky alongside a magical twine (rmu thag). In rites, they alight on prime of tree stands or freshly minimize younger bushes (lha shing) put in on prime of homes and return to the sky afterwards, whereas the ritual specialists chant sonorously the narratives of inbound and out-bound journey of the gods. A twine is hooked up to a lha shing to conduct revitalizing energies of the gods to the earthly beings. Equally, vitality and fertility move down from heaven to the worshippers, certainly into their our bodies. The parable of the primary King descending from the sky unto Ura village, to control Monyul, discovered within the earlier Bhutanese historical past textbooks, echoes this idea. Readers would possibly recall that within the earlier Bhutanese historical past texts, the Dung elites rise in Bumthang and diffuse their community of elites throughout central Bhutan. However the elites’ titles of Dung have been muted in japanese Bhutan for causes but unclear whereas later elite titles of khoche, ponche and chosje unfold. Modernization has flattened the Dung and different conventional households, together with their social and cultural features. A much less structured society, aside from big inequality of earnings, is maybe a loss from a wider standpoint.

It’s noteworthy that Srid-pa’i lha are vegetarian and their ritual simulacrum and edible choices are strictly vegetarian. This actuality is way from the widespread false impression about its mode of worship and criticisms based mostly on such elementary misconceptions that exist amongst many Bhutanese. Meat eaters venture their very own notion on others.

Srid-pa’i lha custom was introduced alongside by individuals referred to as gDung between 1352-54, the years of battle between these warrior clans and the rising centralizing Sakyapa energy in Tibet. Reference to gDung in Lhobrag are happen in 7th and eightth century Tibetan paperwork. gDung has been spelt each with g prefix and with out g prefix, as I do right here. The primary spelling means descendants and the second spelling means primordial. Both method it alludes to unique individuals of a land. gDung have been in all probability, Huber notes, historical clans within the Tibetan plateau, who stood towards stress of transformation wrought elsewhere by Buddhist put up imperial Tibet.

Huber notes that Sakyapa navy leaders distinguished gDung individuals for navy marketing campaign comfort into two sub-groups: Lho gDung and Shar gDung. Lho gDung have been in southern aspect of Tibet close to Phari whereas Shar gDung lived in japanese Lho-brag. Shar gDung migrated to Bumthang and japanese Bhutan and different elements of the japanese Himalayas in the midst of 14th century. Huber notes that Lhobrag Sharchu river valley was the primary centre for Shar gDung communities till they migrated southwards because of Sakyapa’s navy offensive between 1352-54 and destruction of their mkhars. Though historian-monk Ngawang had indicated that Dungs of Bumthang got here from south-western Lhobrag, Huber’s studying of Lha’i gsung rabs present in japanese Bhutan confirmed that ancestors of Zhongar gDung migrated from Lhobrag and Gru-shul by means of one other route, i.e., Nyamjang chu valley. Huber characterizes Lha’i gsung rabs as collective reminiscence of migrant clan inhabitants. Narrative in Lha’i gsung rabs recollects the backward path to totally different areas in Lhobrag which the clans left.

Nevertheless, the in-migration of gDung from adjoining Tibetan highlands doesn’t imply that there have been no pre-existing communities in central and japanese Bhutan. Family tree of Lhase Tsangma’s descendants present that japanese Bhutan was already populated throughout his arrival centuries earlier. Longchen in his 1355 poem about Bhutan (Ura, 2016) notes that Bumthang and Tongsa have been populated, although surprisingly he doesn’t touch upon exodus of gDungs. Huber factors out that the older communities in japanese Bhutan, whom he calls Mon clans included Na clans (Na mi= Na individuals), whose worshipped deities referred to as zhe. For instance, Kurtoed Nay/Nas village was most likely settlement of Na individuals. Autonyms utilizing Na was discovered additionally in Tawang the place Na clan stay at this time. The that means of Naxi individuals residing in Yunnan is similar.

Settlements of Shar gDung in japanese Bhutan are related to their toponyms. Dirang, a Bhutanese territory until Nineteen Thirties, is a corrupted type of Dung-rang Lungpa that Pema Lingpa visited in late fifteenth century. gDung dkar is one other place names which most probably refers to an necessary Shar gDung settlement. It’s even possible that it was initially referred to as gDung mkhar and the identify grew to become Buddhist over time to be all ears to white-conch formed land.

Mkhar (tall stone towers) was an important structure of the gDung. These multi-storied towers are nonetheless present in Lhobrag and Sichuan. Readers will do not forget that mkhars, although shorter and architecturally barely totally different from the classical mkhars of the kind present in Sichuan, have been densely distributed in japanese Bhutan. Carbon courting of timber from the ruins of Tsenkhar la fortress (bTsan-mkar or Mi Zimpa) of Lhase Tsangma traced it again to 1430s. This legendary mkar might have been a consolidation of an earlier construction constructed by Lhase Tsangma.

The climax of the Srid-pa’i lha worship in any village in japanese Bhutan is calendrical competition. Huber initially discovered altogether 52 festivals being carried out in Bhutan and Arunachal. Huber consists of detailed account of such festivals accompanied by instructive excessive decision, and aesthetic diagrams and images.

In his minuscular research inside Bhutan, there’s a sharp concentrate on itineraries, settings and communities surrounding three foremost festivals. These are the Lhamoche of Tsango in Khomachu valley, the Lawa in Kuri chu valley, and the Aheylha of Changmadung in Kholong chu valley. Documentations of those foremost rites are knowledgeable and supported by knowledge collected from the Kharphu competition in Nyimshong in Chamkhar chu valley, and a sequence of rites in Tabi, Gangzur, Zhamling, Shawa, Chengling, Ney, Tangmachu, Da, Bumdeling, Khoma, Ura, Tang, Bemji and several other different festivals in Arunachal. On the whole, he finds that festivals occurring west of Nyimshong in Chamkhar chu valley and so far as Mangde valley has grow to be degraded or ceased to be carried out. He notes that festivals in japanese Bhutan visibly declined within the span of six years whereas he was doing area analysis.

Throughout a competition, the progenitor-lha is invited to descend from the sky into the midst of the related clans and lineages. In each competition a hereditary ritual knowledgeable who can chant rabs, the narrative of the lha’s attributes and journey itinerary, leads the occasion. Huber notes that there are a lot of variations of rabs, and they’re dynamic in that artistic ritual consultants would possibly spontaneously add to them within the second of efficiency. Contemplating that the follow is devoted to the fecundity and vitality of males and animal, each home and sport, representations of human and animal sexuality, full nudity in sure performances, with none unease of the prudish, have been the norm prior to now.

Jambay Lhakhang drub with its midnight nude-with-mask tercham used to attract throngs of winter vacationers briefly flooding the resorts and homes and draining cash into the communities of Choskhor. Genuine festivals of japanese Bhutan might maintain each is tradition and livelihoods many instances extra. However no one will fly hundreds of miles simply to take a look at seashore shorts, or any newly fabricated ceremony.

Three nights of a competition have been demarcated from the conventional: individuals gave permission to themselves to be free to take pleasure in with none inhibitions and disgrace. These competition communities preserve that the regime of Zhabdrung was conceded rule over the nation, however not over the three days and nights of celebrations. This mutually agreed time period should go on, actually inspired enthusiastically, if our cultures are to not get impoverished by numbing homogeneity. A common pattern in our nation has been dissemination and thriving of the identical set of dances in several festivals somewhere else, flattening creativity, depth, and variety. Huber’s splendid two volumes generally is a turning level within the revival of those particular festivals in japanese Bhutan or a documentation of extinct cultures.

Contributed by

Dasho Karma Ura, Ph D

[ad_2]

Source link