[ad_1]

(JTA) — It’s exhausting to discover a poster selling early Twentieth-century Zionism that doesn’t depict a tanned, chiseled man toting a shovel or a gun. The posters had been visible reinforcement of the “Muscle Jewry” valued by Max Nordau and different early Zionist leaders, who felt the land would redeem a bodily depleted Jewish individuals and the individuals would renew a uncared for land.

One early Zionist thinker defied this macho picture, after which some: “Whereas Zionism celebrated robust and wholesome our bodies,” Jessie Sampter “spoke of herself as ‘crippled’ from polio and stricken by weak spot and illness her entire life.” As well as, “she wrote of homoerotic longings and had same-sex relationships we might contemplate queer.”

These quotes are from Sarah Imhoff’s new biography, “The Lives of Jessie Sampter: Queer, Disabled, Zionist” (Duke College Press). The e-book explores the lifetime of a New York-born poet and author (1883–1938) who moved to Palestine in 1919 and whose circle earlier than and after included Henrietta Szold, who based Hadassah; Rabbi Mordecai Kaplan, the founding father of Reconstructionist Judaism; Louis Brandeis, the longer term U.S. Supreme Courtroom justice and chief of the Zionist Group of America; the author Mary Antin, and Albert Einstein.

Though Sampter by no means turned a family identify, she revealed 11 books and dozens of poems in English and Hebrew. She shared a house at Kibbutz Givat Brenner with the Russian Zionist Leah Berlin, and advocated on behalf of Yemenite Jews and the pre-state Jewish group’s deaf inhabitants. She by no means married nor bore kids, though she did undertake a Yemenite Jewish daughter. Her story is value remembering, writes Imhoff, as a result of Sampter’s life itself represented an alternate imaginative and prescient of Zionism — one which “didn’t comply with the gender norms prescribed for the best (male) Zionist builder or the feminine Zionist nurturer of the nation.”

Imhoff is affiliate professor of Spiritual Research at Indiana College, Bloomington, and creator of “Masculinity and the Making of American Judaism.” We spoke by way of Zoom on Thursday.

Our dialog was edited for size and readability.

New York Jewish Week: I had by no means heard of Jessie Sampter. When did you come to know her and determine she was a topic to be written about?

Sarah Imhoff: My first e-book was about masculinity and American Judaism. I had loads of males speaking about Zionism and masculinity, and I used to be questioning what ladies, particularly American Jewish ladies, considered Zionism and masculinity. I knew that Sampter was a Zionist, so I obtained maintain of a few of her recordsdata in Jerusalem. She didn’t even have that a lot to say about masculinity and Zionism, however I used to be completely captivated

Earlier than we get to her Zionism, let’s place her in New York, the form of household she was born into and the best way she grew up.

She was born in Harlem. She grew up with two dad and mom who had been German Jewish and pretty center class. They belonged to the Moral Tradition motion with different acculturated Jews. They spoke English at residence, that they had a Christmas tree at residence, at the very least typically. They’re built-in into what I consider as a Jewish tradition.

Regardless that they didn’t ascribe to Judaism itself.

Jessie has this story about when she was maybe 8 years outdated. Anyone mentioned, “You’re a Jew!” And she or he replied, “No, I’m not!” and went residence crying. After which her dad and mom informed her, “Effectively, really, we’re Jewish,” however it doesn’t seem to be that was a serious method they talked about themselves.

And as she grew up she turned what we would name a seeker — exploring Japanese religions, seances, Transcendentalism, Ouija boards — however what you like to explain by way of “non secular recombination.”

I like that as a metaphor, as a result of it means that what you find yourself with is definitely a complete factor, moderately than what some seek advice from as a “cafeteria faith,” which could be a little condescending. When individuals take into consideration “how do I perceive the world” they draw on issues that we might hint to totally different non secular traditions. She doesn’t go “faith hopping,” however has this early lifetime of being very keen on faith, however not understanding the place she matches. After which, curiously, she involves Zionism earlier than she involves Judaism, which is a comparatively uncommon factor.

Inform me somewhat bit extra about that. How outdated is she at that time?

She is certainly there by 1914, so her mid-to-late 20s. Many individuals at that second are occupied with nationalism, and never essentially in the best way that we take into consideration nationalism. We would say “peoplehood.” One of many issues she likes about Zionism is it imagines Jews as a individuals the best way Mordecai Kaplan did, and she or he and Kaplan are sometimes in touch.

She thinks that Jews as a individuals have one thing distinctive to contribute to the undertaking of humanity. She would additionally say that each individuals has one thing distinctive to contribute to the undertaking of humanity, however a part of our objective is to determine what that’s, and every individuals will be its personal individuals after which we’ll all be stronger collectively. After which she thinks, effectively, if a part of what the Jewish individuals has to supply is a biblical custom, or prophetic custom, I ought to discover Judaism.

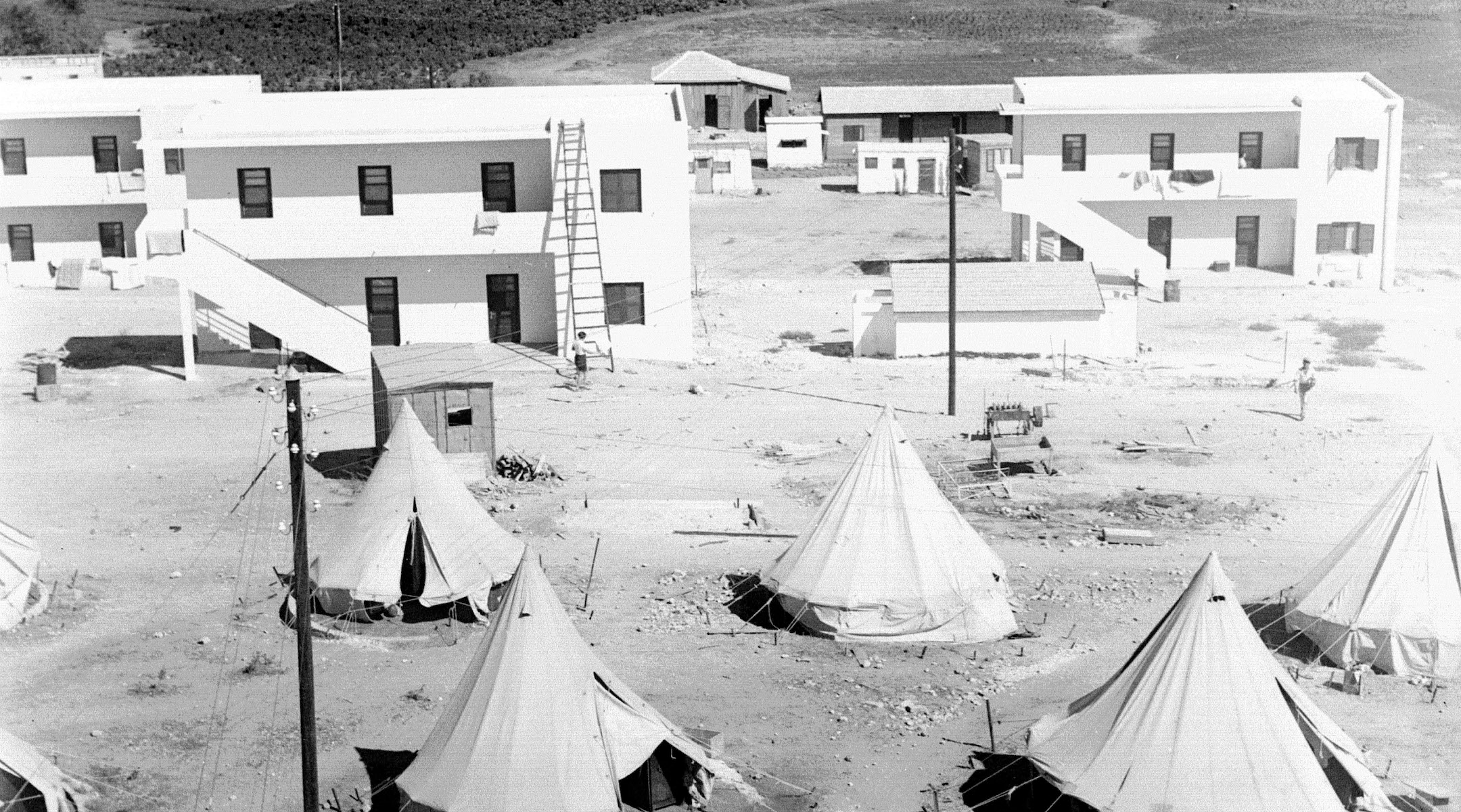

Jessie Sampter lived at Kibbutz Givat Brenner, proven above in 1935, till her loss of life in 1938. (Israel Authorities Press Workplace)

And but, she’s a single lady within the early Twentieth century, when not a number of Individuals had been keen to sail internationally and turn into a pioneer in a form of backwater nation. The place does she get the impulse?

That’s an important query. A Zionist good friend of hers, Lotta Levensohn, calls its a “malarial swamp.” Sampter was attempting to persuade the Zionist Group of America to ship her and initially they mentioned no, however ultimately she satisfied Brandeis. That’s how she narrates it, anyway. And she or he goes on a one-year contract the place she’ll be writing they usually’ll be paying her to write down, and even when she goes she is pondering that staying is her plan. She writes that she is “getting married” to Palestine. I believe it’s audacious, particularly as a result of she’s disabled with what I believe is post-polio syndrome. Principally proper after she lands she results in Hadassah Hospital in Jerusalem for just a few weeks recuperating.

She obtained polio when she was 12. Describe her incapacity and the way she offered bodily both to others or to herself.

If you happen to see a photograph of her it’s not apparent, though she’s usually holding her personal wrist or placing her fingers behind her again. There aren’t any motion pictures of her; she’s nearly all the time sitting in a chair or posed standing nonetheless. If you happen to simply checked out her at one prompt, you wouldn’t see incapacity. However if you happen to interacted along with her at any size, you most likely would.

And she or he undoubtedly had limitations by way of strolling, or working along with her fingers, and whereas she liked working in her backyard there have been limits on what she might do.

Proper. And people are issues which are way more urgent in Palestine than they’re in New York.

And that’s as a result of the pioneers had been anticipated to work and construct the homeland with their fingers and backs as “muscle Jews.”

That concept permeates a number of Jewish settlement in Palestine at the moment. She’s concerned somewhat bit within the scouting motion, which is about making little muscle Jews: “We’re gonna go mountaineering, you’re gonna study to construct the nation.” That permeates nearly all the Zionist propaganda that you would be able to see within the U.S. and in Europe, too.

And is she very a lot conscious that she’s in a contradiction with the traditional Zionism of the day?

Sure, she is. There are moments once I see her in her writing pushing towards it. She’s concerned with early deaf training in Palestine, and she or he thinks deaf individuals can develop as much as be actual, central residents when others didn’t. She’s concerned in Yemenite training, too. She insists on a democratic strategy that claims the Yemenite housewife is identical because the male European halutz [pioneer], and she or he says — and these can be my phrases — that we wish a extra inclusive Zionism with respect to our bodies.

However she has a number of self doubt. There are moments the place she’s very cognizant of not becoming in and, possibly in that second, buys into the Zionist perfect of wholesome, robust our bodies.

If her bodily limitations set her aside, I think about her sexual identification would too. That is additionally in a group the place procreation is taken into account a Zionist tenet.

I’ve wrestled with this rather a lot. I wouldn’t say she has a transparent identification. I wouldn’t, for instance, name her lesbian, as a result of she wouldn’t have self-described that method. There are two issues that I believe make it proper to consider her in queer phrases. Her father died when she was younger, her mom died not lengthy after. And she or he created what queer theorists usually consider as a selected household. She met Leah Berlin very quickly after shifting to Palestine, and the 2 of them reside collectively more often than not. They lived aside for somewhat bit after which they moved again in collectively and made monetary selections, wish to go to Kibbutz Givat Brenner collectively. She adopted a Yemenite orphan named Tamar. And Leah would go to Tamar when she was somewhat older and away at college.

It’s not like she has no organic household — she writes a ton of letters to her sister Elvie — however there are these kinship buildings that look very very similar to chosen household they usually’re queer kinship buildings.

I do not know if she ever had intercourse with Leah Berlin. But it surely’s not widespread for girls of the time to write down about intercourse acts, interval. However she expresses what I name queer need, whether or not fantasizing being married to a lady playmate or all the time eager to be the soldier when she was enjoying. There are erotic ways in which she describes a friendship with one other lady.

A 1954 poster from Israel’s nationwide commerce union celebrates the position of guide labor in constructing the Jewish state. (Swim Ink 2, LLC/CORBIS/Corbis by way of Getty Photos)

How was she seen in Palestine or on the kibbutz? Maybe as a “spinster,” or was her relationship with Leah Berlin understood as one thing else and simply type of tolerated?

When she’s occupied with becoming a member of the kibbutz, it’s clear that it’s double or nothing: They get the pair of them or they get nobody. They’re coming collectively.

You referenced Tamar, the Yemenite toddler that she adopts. How uncommon was that? And I believe we should always say this isn’t within the Nineteen Fifties, when the Ashkenazi elite had been accused of separating Yemenite children from their beginning dad and mom.

It’s not that, however there may be nonetheless an undergirding of cultural assumptions about Ashkenazi tradition being extra civilized or higher than Yemenite tradition. This was not a part of that very same story, however it clearly has connections. However Sampter was concerned in Yemenite training, like establishing a Yemenite kindergarten, so she actually cared about Yemenite children and girls.

Adopting a Yemenite youngster was comparatively uncommon. A few of her pals suppose it’s a horrible thought. Even Henrietta Szold says, “How are you going to care for this child? You may barely care for your self.”

Talking of Henrietta Szold, in 1915 Sampter writes a type of Zionist textbook for Hadassah, “Course in Zionism.” Inform me about her relationship with Szold and the ladies’s Zionist motion.

Her relationship with Szold started earlier than that textbook, going again to one thing like 1910 or 1911. Sempter seems to be as much as Szold and Szold additionally acknowledges one thing in Sampter. They fight having her be a speaker for Hadassah and I believe for causes associated to her incapacity that simply doesn’t fly. I’m additionally unsure Sampter was very charismatic. She may need actually been a form of tough particular person. However fairly early on in her personal Zionist growth she is writing for Hadassah. Sampter thinks of Szold as a mentor, and even tries out being somewhat bit extra Orthodox, however then form of backs off somewhat bit later.

She died in 1938, 10 years earlier than statehood, however already the armed wrestle towards the Arabs and the British answerable for Palestine had begun. You write that she was a pacifist who supported Jewish armed protection in Palestine.

She purchased a gun at one level. She was like, “I do not know the right way to shoot it, however I’m gonna put it right here in case someone wants to come back in and use it.” She’s a pacifist besides that she believes that typically we would must defend ourselves. Her place strikes backwards and forwards. She experiences a number of the armed battle in Palestine, though it’s clear she thinks the actual dangerous guys are the British, who she thinks are establishing Jews and Arabs to combat it out for sources and land.

She has moments of being extra and understanding of Arabs than a few of her contemporaries. After which she additionally has moments of claiming that the Arabs have extra to study from Jews than Jews should study from them. It’s not fairly as one sided as it’s for a lot of others. Alternatively, it’s clear which aspect has her primary loyalty.

She had quite a few well-known pals, however once more, she’s hardly as well-known in the present day as they’re. What about her physique of labor would possibly nonetheless be priceless or value understanding about in the present day?

What’s compelling is somewhat bit about her physique of labor and somewhat bit about her personal story. She makes us take into consideration the actual number of potentialities for Zionism. I believe, in the present day, Zionism has a a lot narrower set of meanings than it did in Sampter’s time. She gestures towards different potentialities.

Give me an instance. How did she broaden the definition of Zionism?

I believe the incapacity instance, which incorporates each her personal life and what she wrote, exhibits us that there are methods of imagining society that don’t should privilege an able-bodied, frankly male imaginative and prescient of society. Additionally, “Mizrahi” wasn’t purposeful at the moment, however her Zionism does actually strive to consider how the Yemenite Jews and Moroccan Jews match into it. The Zionist imaginative and prescient that prevailed in Israel was an Ashkenazi one. Her instance may very well be a useful resource for individuals who would possibly wish to think about the up to date state of Israel in numerous methods.

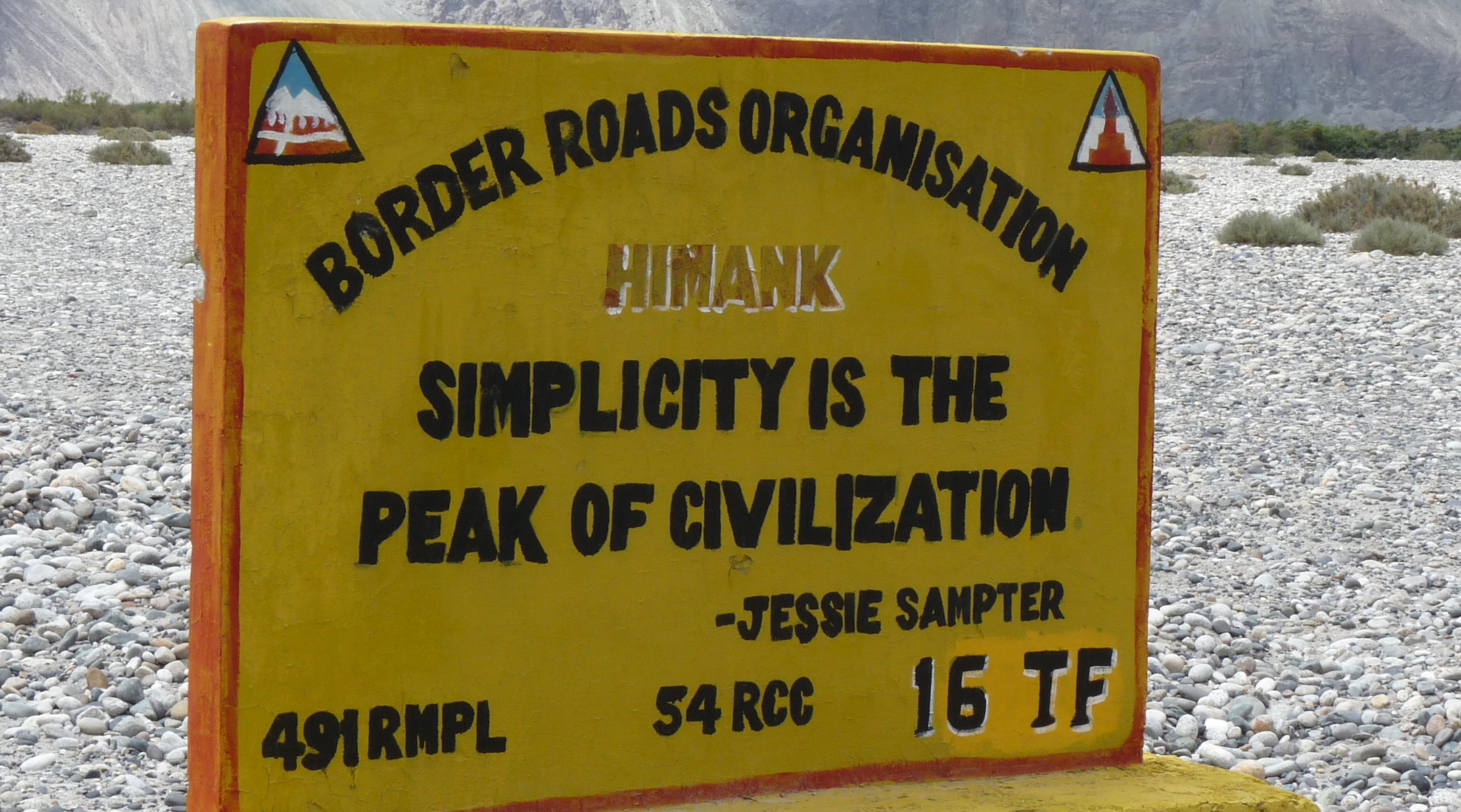

One in every of Jessie Sampter’s quotes, taken from certainly one of her poems and popularized in a e-book of quotations by ladies, seems on an indication in Ladakh, India. (Wikipedia)

You write that after she died Sampter turned a “quotable thinker, showing in Weight Watchers inspirational books, on web sites and on a roadside in India.” What kind of quotes appealed to popular culture?

Most of these are literally the identical quote, which is “simplicity is the height of civilization,” which is weirdly in the course of a poem. So I believed that’s form of unusual. How did Weight Watchers get this factor? I traced it again to a rabbi who was doing a set of quotes of Jewish ladies. I did actually go looking for the street register India. I believe the web performs a job in why so many picked up that one quote.

How else can we entry her in the present day? Are any of her books in print? Is there a monument to her?

Some people at Givat Brenner nonetheless bear in mind her and nonetheless inform tales about her. The remaining home she helped discovered continues to be standing, though it’s not a relaxation home. I don’t know if any of her books are in print. She’s not very effectively remembered. I believe there are causes for that. I believe her being single is definitely certainly one of them. It’s usually households which are good at memorializing and publicizing the significance of individuals. And I believe it’s as a result of her Zionism was not really the Zionism that obtained picked up because the mainstream. She doesn’t match what individuals think about that group of pioneers to be.

My argument within the e-book will not be that “right here’s this actually influential lady we’ve forgotten.” It’s nearly, “look, this lady wrote all of these items, and was very well linked, and wasn’t influential. However she exhibits us these roads not taken.”

is editor in chief of The New York Jewish Week and senior editor of the Jewish Telegraphic Company.

The views and opinions expressed on this article are these of the creator and don’t essentially replicate the views of JTA or its father or mother firm, 70 Faces Media.

[ad_2]

Source link