[ad_1]

(JTA) — Earlier this month the New York Instances convened what it known as a “focus group of Jewish People.” I used to be struck briefly by that phrase — Jewish People — partially as a result of the Instances, just like the Jewish Telegraphic Company, tends to favor “American Jews.”

It’s seemingly a distinction with out a distinction, though I do know others may disagree. There’s an argument that “American Jew” smacks of disloyalty, describing a Jew who occurs to be American. “Jewish American,” based on this considering, flips the script: an American who occurs to be Jewish.

If pressed, I’d say I favor “American Jew.” The noun “Jew” sounds, to my ear anyway, extra direct and extra assertive than the tentative adjective “Jewish.” It’s additionally in line with the way in which JTA essentializes “Jew” in its protection, as in British Jew, French Jew, LGBT Jew or Jew of shade.

I wouldn’t have given additional thought to the topic if not for a webinar final week given by Arnold Eisen, the chancellor emeritus on the Jewish Theological Seminary. In “Jewish-American, American-Jew: The Complexities and Joys of Dwelling a Hyphenated Identification,” Eisen mentioned how a debate over language is de facto about how Jews navigate between competing identities.

“What does the ‘American’ signify to us?” he requested. “What does the ‘Jewish’ signify and what’s the nature of the connection between the 2? Is it a synthesis? Is it a pressure, or a contradiction, or is it a blurring of the boundaries such you can’t inform the place one ends and the opposite begins?”

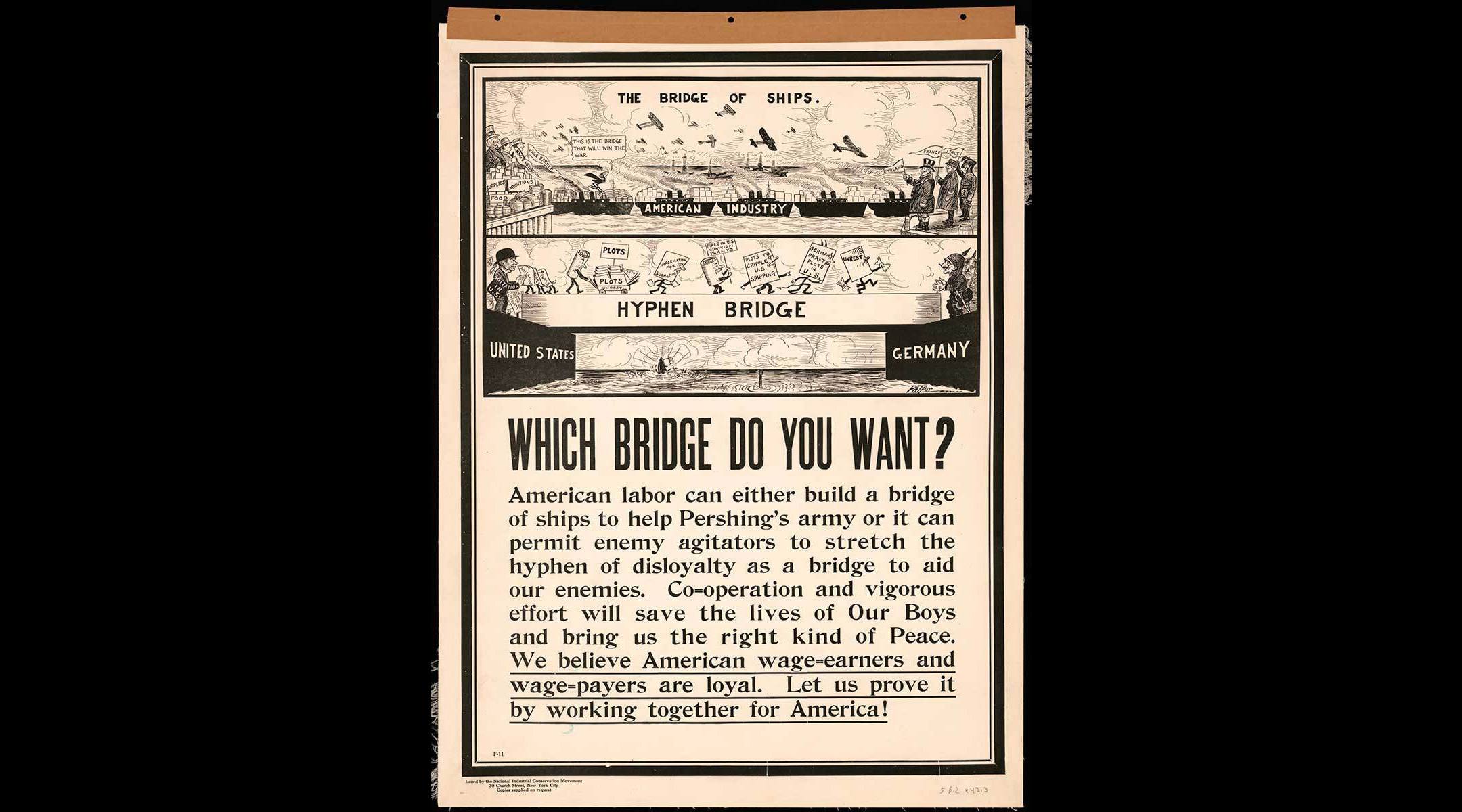

Questions like these, it seems, have been requested since Jews and different immigrants first started flooding Ellis Island. Teddy Roosevelt complained in 1915 that “there isn’t any room on this nation for hyphenated People.” Woodrow Wilson preferred to say that “any man who carries a hyphen about with him carries a dagger that he’s able to plunge into the vitals of the Republic.” The 2 presidents have been frankly freaked out about what we now name multiculturalism, satisfied that America couldn’t survive a wave of immigrants with twin loyalties.

The 2 presidents misplaced the argument, and for a lot of the Twentieth century “hyphenated American” was shorthand for profitable acculturation. Whereas immigration hardliners proceed to query the loyalty of minorities who declare multiple identification, and Donald Trump performed with the politics of loyalty in remarks about Mexicans, Muslims and Jews, ethnic delight is as American as, properly, St. Patrick’s Day. “I’m the proud daughter of Indian immigrants,” former South Carolina Gov. Nikki Haley mentioned in asserting her run for the Republican presidential nomination this month.

For Jews, nonetheless, the hyphen grew to become what philosophy professor Berel Lang known as “a weighty image of the divided lifetime of Diaspora Jewry.” Jewishness isn’t a distant nation with quaint customs, however a faith and a transportable identification that lives uneasily alongside your nationality. In a 2005 essay, Lang argued that on both facet of the hyphen have been “vying traditions or allegiances,” with the Jew continually confronted with a alternative between the American facet, or assimilation, and the Jewish facet, or remaining distinct.

Eisen calls this the “query of Jewish distinction.” Eisen grew up in an observant Jewish household in Philadelphia, and understood from an early age that his household was totally different from their Vietnamese-, Italian-, Ukrainian- and African-American neighbors. Alternatively, they have been all the identical — that’s, American — as a result of they have been all hyphenated. “Being parallel to all these different variations, gave me my place within the metropolis and within the nation,” he mentioned.

In faculty he studied the Jewish heavy hitters who have been much less sanguine in regards to the integration of American and Jewish identities. Eisen calls Rabbi Mordecai Kaplan, the renegade theologian at JTS, “the thinker who actually made this query uppermost for American Jews.” Kaplan wrote in 1934 that Jewishness may solely survive as a “subordinate civilization” in america, and that the “Jew in America will probably be before everything an American, and solely secondarily a Jew.”

Kaplan’s prescription was a most effort on the a part of Jews to “save the otherness of Jewish life” – not simply by synagogue, however by a Jewish “civilization” expressed in social relationships, leisure actions and a conventional ethical and moral code.

In fact, Kaplan additionally understood that there was one other method to defend Jewish distinctiveness: transfer to Israel.

A poster issued by the Nationwide Industrial Conservation Motion in 1917 warns that the American battle effort is likely to be harmed by a “hyphen of disloyalty,” suggesting immigrants with ties to their homelands have been working to help the enemy. (Prints and Images Division, Library of Congress)

The political scientist Charles Liebman, in “The Ambivalent American Jew” (1973), argued that Jews in america have been torn between surviving as a definite ethnic group and integrating into the bigger society.

In response to Eisen, Liebman believed that “Jews who make ‘Jewish’ the adjective and ‘American’ the noun are inclined to fall on the mixing facet of the hyphen. And Jews who make ‘Jew’ the noun and ‘American’ the adjective are inclined to fall on the survival facet of the hyphen.”

Eisen, a professor of Jewish thought at JTS, famous that the problem of the hyphen was felt by rabbis on reverse ends of the theological spectrum. He cited Eugene Borowitz, the influential Reform rabbi, who steered in 1973 that Jews in america “are literally extra Jewish on the within than they fake to be on the skin. In different phrases, we’re so fearful about what Liebman known as integration into America that we conceal our distinctiveness.” Rabbi Joseph Soloveitchik, the main Trendy Orthodox thinker of his era, despaired that america offered its Jews with an unresolvable battle between the individual of religion and the individual of secular tradition.

Once I learn the texts Eisen shared, I see Twentieth-century Jewish males who doubted Jews might be totally at residence in America and at residence with themselves as Jews (not to mention as Jews who weren’t straight or white — which might demand just a few extra hyphens). They couldn’t think about a wealthy Jewishness that didn’t exist as a counterculture, the way in which Cynthia Ozick questioned what it will be prefer to “suppose as a Jew” in a non-Jewish language like English.

They couldn’t image the hyphen as a plus signal, which pulled the phrases “Jewish” and “American” collectively.

Latest traits assist the skeptics. Have a look at Judaism’s Conservative motion, whose rabbis are educated at JTS, and which has lengthy tried to reconcile Jewish literacy and observance with the American mainstream. It’s shrinking, shedding market share and followers each to Reform — the place the American facet of the hyphen is ascendant — and to Orthodoxy, the place Jewish otherness is booming in locations like Brooklyn and Lakewood, New Jersey. And the Jewish “nones” — these opting out of faith, synagogue and energetic engagement in Jewish establishments and affairs — are among the many fastest-growing segments of American Jewish life.

Eisen seems extra optimistic a few hyphenated Jewish identification, though he insists that it takes work to domesticate the Jewish facet. “I don’t suppose there’s something at stake essentially on which facet of the hyphen you place the Jewish on,” he mentioned. “However if you happen to don’t exit of your method to put added weight on the Jewish within the pure course of occasions, as Kaplan mentioned accurately 100 years in the past, the American will win.”

is is Editor at Giant of the New York Jewish Week and Managing Editor for Concepts for the Jewish Telegraphic Company.

The views and opinions expressed on this article are these of the creator and don’t essentially replicate the views of JTA or its guardian firm, 70 Faces Media.

[ad_2]

Source link