[ad_1]

NOVI SAD, Serbia (JTA) — Within the coronary heart of downtown in Serbia’s second-largest metropolis, nestled between brick buildings on a leafy avenue, sits a big synagogue.

With its 130-foot-high central dome and light yellow brick facade, together with its Jewish college and places of work on both facet, the synagogue’s three-building advanced has change into a must-see vacationer attraction, with multilingual panels in its courtyard explaining the realm’s Jewish historical past.

The synagogue was constructed to accommodate as much as 950 worshippers within the first decade of the twentieth century. However like the town and Serbia extra broadly, the constructing has clearly seen higher days. On two latest days, a household was camped exterior the doorway, begging passersby for cash.

Earlier than World Battle II, Novi Unhappy had roughly 60,000 inhabitants, 4,300 of whom had been Jews — about 7% of the whole inhabitants. Most had been prosperous retailers, legal professionals, medical doctors and professors. Their wealth was mirrored within the metropolis’s opulent synagogue, constructed between 1906 and 1909 by Hungarian Jewish architect Lipot Baumhorn, whose work integrated components of the Artwork Nouveau motion.

Right this moment, nonetheless, the outstanding constructing serves a dwindling neighborhood that, like others decimated by the Holocaust and additional eroded by the Balkan wars of the Nineties, fears for its future as residents disperse overseas. Solely about 640 Jews stay in Novi Unhappy; others have sought a future in Israel or international locations that supply extra financial alternative.

“We use our personal shul just for Yom Kippur,” mentioned Novi Unhappy native Ladislav Trajer, the deputy president of the Federation of Jewish Communities of Serbia.

“We get six to 10 folks for Shabbat — perhaps 15 — however fewer than half are male so we are able to’t make a minyan,” mentioned Trajer, referencing a Jewish prayer quorum of 10 males. He spent eight years in Israel and in addition served within the Israel Protection Forces. “Even in Belgrade, which is way bigger, the rabbi doesn’t at all times get a minyan. And no person right here retains kosher. You possibly can’t get kosher meat.”

A view of Novi Unhappy from the Petrovaradin Fortress. (Zoran Strajin/Wikimedia Commons)

Novi Unhappy was a thriving middle of Jewish life in prewar Yugoslavia and the town — now a metropolis of 370,000 generally referred to as the “Serbian Athens” — was named a European Tradition Capital of 2022 for its arts, meals, structure and different cultural scenes.

However most native Jews see few prospects for themselves in a rustic beset by financial turmoil. Between 1990 and 2000 — following Yugoslavia’s collapse; the ethnic wars in Croatia, Bosnia and later Kosovo; and the imposition of crippling sanctions by america, the European Union and the United Nations — Serbia’s GDP tumbled from $24 billion to $8.7 billion. By 1993, almost 40% of Serbia’s folks had been residing on lower than $2 a day, and at current, the typical Serb earns roughly $430 to $540 a month.

Regardless of these difficulties, Serbia agreed in 2017 to pay simply over $1 million yearly over the following 25 years to its remaining Jews as compensation for property nationalized by the postwar communist regime. Half of that cash goes on to Jewish neighborhood organizations, 20% to Holocaust survivors and the remaining 30% to initiatives that purpose to protect Jewish traditions.

Ladislav Trajer, left, and Mirko Štark, the highest two leaders of the Jewish neighborhood in Novi Unhappy, chat simply exterior the doorway to their synagogue. (Larry Luxner)

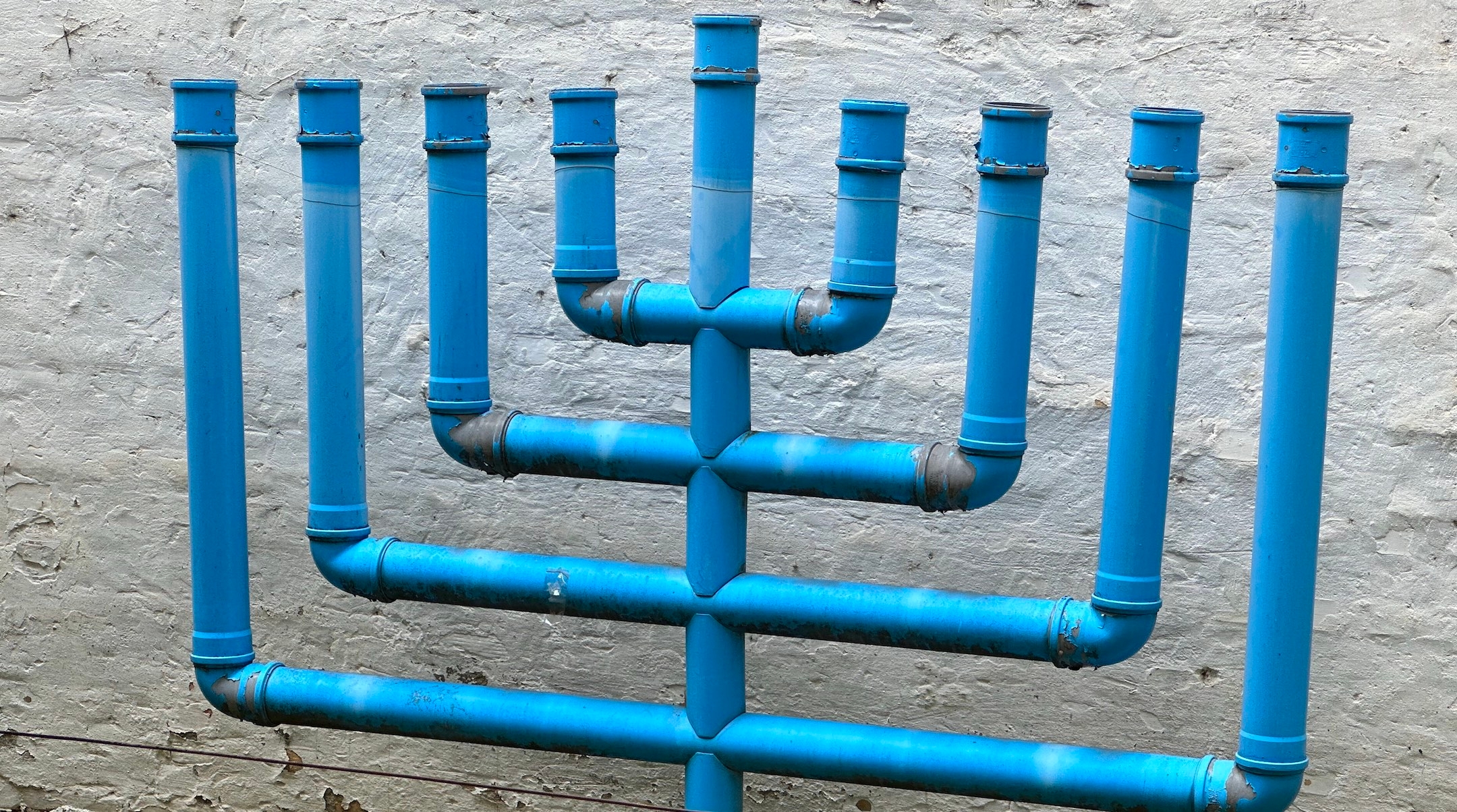

Since 2012, the Novi Unhappy neighborhood has additionally earned earnings by renting out its large synagogue to the municipality for classical music concert events. In return, the town maintains the advanced as a historic monument, and it’s now repairing the synagogue’s roof and fixing leaky water pipes.

“These buildings had been near collapse,” mentioned Trajer. He added that the town’s uncared for Jewish cemetery can appear to be a forest. “So we’re slicing the timber and struggling to place up fences.”

Though antisemitic incidents are usually not too frequent, Serbia, like most different international locations in Jap Europe, additionally contends with a robust nationalist streak. Trajer, who screens antisemitism carefully, mentioned round 1,500 Serbs belong to extremist teams, of which maybe 120 are energetic. Serbian Motion, a small group of neo-Nazis, often holds rallies and spray-paints antisemitic, anti-immigrant and anti-gay graffiti on public buildings.

“In highschool, my historical past professor joked that Hitler couldn’t get into an artwork academy, and that’s why he determined to kill the Jews,” mentioned Teodora Paljic, a 20-year-old Jewish college scholar. “I don’t discuss these items with folks I don’t really feel secure round.”

She mentioned that “Life in Serbia may be very tough” as a result of “all the costs have gone up, however salaries haven’t elevated since 2019.”

Trajer says the neighborhood is working to scrub up the town’s Jewish cemetery. (Larry Luxner)

Novi Unhappy is the capital of Vojvodina, an autonomous province that covers a lot of northern Serbia, and on the native Jewish neighborhood’s zenith, 86 synagogues flourished within the province. Right this moment, solely 11 stay standing, and most have fallen into disuse.

Mirko Štark, president of the Jewish Neighborhood of Novi Unhappy, mentioned Jews first settled within the metropolis within the seventeenth century, shortly after its founding in 1694 below the Hapsburg monarchy.

“When the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the place most Ashkenazim lived, launched new legal guidelines that restricted Jews from residing in cities, many individuals ran to the border space, the place these legal guidelines weren’t so strictly enforced,” Štark mentioned. Later, when the Serbs captured Vojvodina, these restrictions had been rescinded, and the Jewish neighborhood blossomed.

Following World Battle I and the institution of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes — later Yugoslavia — Novi Unhappy’s Jews loved a cultural and financial renaissance that noticed the formation of a Jewish neighborhood middle, athletic golf equipment, choirs and a number of other Jewish newspapers.

That renaissance ended abruptly in 1941, when the Hungarian military, in collaboration with Nazi Germany, occupied Novi Unhappy, making life for Jews insupportable. Over a three-day interval in January 1942 now often called the Novi Unhappy Bloodbath, the Hungarians rounded up greater than 1,400 Jews, seized their property, shot them of their backs and threw them into the freezing Danube River.

After Hungary’s capitulation to Germany, armed guards herded the town’s remaining 1,800 Jews into the synagogue and stored them there for 2 days in deplorable circumstances with out meals or water. On April 27, 1944, the Nazis marched their weakened Jewish captives to the practice station, then compelled them on a practice to Auschwitz that took two months to reach because of Allied bombing.

College scholar Teodora Paljic, 20, helps organize cultural applications for Jewish youth in Novi Unhappy. (Larry Luxner)

Solely 300 of Novi Unhappy’s Jews survived the Holocaust, and rebuilt the neighborhood nearly from scratch within the ensuing postwar chaos.

“There have been no spiritual folks anymore, and no rabbi,” mentioned Štark. “Many went to Israel within the first aliyah. The small variety of Jews remaining tried to maintain the neighborhood alive, opening a kitchen to supply meals for individuals who couldn’t purchase for themselves. My grandmother survived Auschwitz. She labored in that kitchen.”

In accordance with Trajer, from 1948 to 2022, no Shabbat companies had been held. Nowadays, Trajer conducts all spiritual companies as a result of he’s the one one who is aware of the Hebrew prayers fluently.

A view of the inside of the Novi Unhappy synagogue. (Larry Luxner)

With 640 members, Novi Unhappy has the nation’s second-largest Jewish inhabitants after Belgrade. The capital is dwelling to greater than half of the nation’s 3,000 Jews, out of a complete inhabitants of seven.1 million. Smaller Jewish communities can be present in Subotica, Niš and different cities. Solely the synagogues in Belgrade and Subotica — the latter situated a couple of miles from the Hungarian border — nonetheless perform.

Most members of the Novi Unhappy neighborhood, together with Štark, have married non-Jews.

“My spouse shouldn’t be Jewish. Neither was my mom. Solely my father was Jewish,” he mentioned. “After World Battle II, the alternatives for locating husbands and wives inside the neighborhood was restricted. For that reason, we settle for non-Jewish spouses as members. That is the one solution to survive.”

Štark, 70, is a retired professor of media manufacturing who labored for years at Novi Unhappy’s predominant TV station. He’s additionally the longtime president of the synagogue’s choir, HaShira, which sings in Hebrew, Ladino and Yiddish and lately received an award for its performances in neighboring Montenegro. Solely three of the choir’s 35 members are Jews.

“Once I started my mandate as president a 12 months and a half in the past, we awakened many actions within the Jewish neighborhood that had existed solely on a small scale earlier than,” he mentioned.

A makeshift nine-branched menorah contructed from recycled water pipes is seen exterior the synagogue in Novi Unhappy. (Larry Luxner)

In addition to the choir, these embody the Zmaya dance troupe in addition to a Jewish tradition membership that meets each Tuesday at 6 p.m. to debate books and Israeli motion pictures. There’s additionally a “child membership” for babies and one other membership for teenagers, whose actions are led by two adults. Hanukkah and Passover are celebrated by households collectively, and on Tu B’Shvat, the neighborhood vegetation timber.

The neighborhood can also be investing in its members, and Paljic is emblematic of that hope.

Paljic, interviewed on the stylish Café Petrus, a 15-minute stroll from Novi Unhappy’s Jewish cemetery, is the daughter of Jewish mother and father who met at a Purim get together in Belgrade.

“My grandparents had been killed in Jasenovac [a notoriously brutal concentration camp], however my greatest pal’s grandmother survived Auschwitz,” she mentioned. “The issue is, folks don’t discuss Judaism as a result of they’re scared. There may be nonetheless antisemitism. Final 12 months, someone drew a swastika on the entrance to the Jewish cemetery in Belgrade. We had been all shocked.”

This summer time, Paljic labored as a counselor at Hungary’s Camp Szarvas, which brings collectively younger Jews from all through Central and Jap Europe. The camp welcomed 20 kids from Novi Unhappy this 12 months; the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee paid their tuition.

Whereas she wish to be near her household, Paljic mentioned she have to be sensible.

“I need to go someplace exterior Serbia after I end school,” she mentioned. “I don’t see my profession right here. I like artwork historical past and pictures, however there’s no cash in that in Serbia.”

Regardless of the challenges, Štark isn’t able to say kaddish for Novi Unhappy’s Jews simply but.

“We’ll maintain the Jewish spirit alive right here. We’re working onerous, beginning with the kids,” he mentioned. “If we don’t, the whole lot will die in 5 or 10 years. So it will depend on us.”

[ad_2]

Source link