[ad_1]

(New York Jewish Week) — When Jennifer Baum’s dad and mom purchased their three-bedroom, postwar condo on the Higher West Aspect in 1967, they paid $3,800 — a discount even on the time, when the neighborhood was nonetheless gritty and New York on the cusp of steep decline.

For a middle-class Jewish couple dedicated to dwelling within the metropolis the place they grew up, the 14th flooring condo at RNA Home, a 212-unit concrete slab on West 96th Road, was a dream come true. Their two daughters might develop up in a various neighborhood, a block and half from Central Park and a stroll or subway journey from all that town needed to supply.

It was a dream made potential by a state and metropolis program that sponsored middle-income leases and co-ops throughout New York from the Nineteen Fifties up till the fiscal disaster of the late ’70s. When the center class was fleeing to the suburbs, the Mitchell-Lama Housing Program (named for the politicians who championed it in 1955) was a boon for folks too well-off to qualify for public housing and too poor to afford market-rate houses.

“It celebrated the concept of the frequent good,” Baum instructed me in an interview. “It was a really complete, uncommon experiment that enabled the Higher West Aspect to retain a sense of variety — economically, culturally — at a time when authorities actually believed in attempting to make town a livable place for all.”

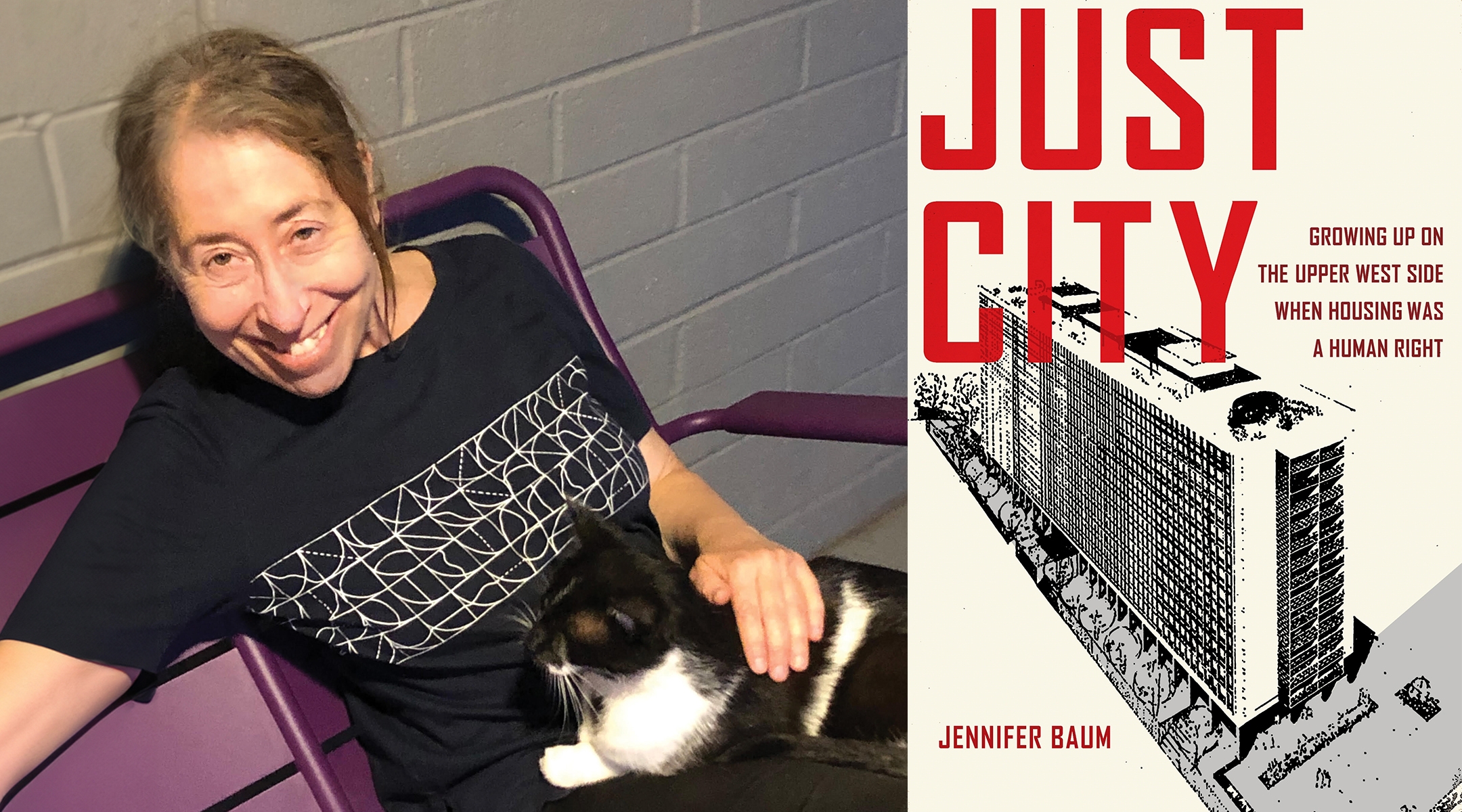

Baum writes about rising up in a Mitchell-Lama constructing in “Simply Metropolis: Rising Up on the Higher West Aspect When Housing Was a Human Proper.” A memoir for which Baum took a deep dive into the historical past of metropolis housing, the brand new guide arrives as cities corresponding to New York face an inexpensive housing disaster — and simply as New York state legislators are calling for “Mitchell-Lama 2.0.” The state Senate’s “One Home” finances proposal consists of the creation of a housing company to finance a mixture of new inexpensive leases and co-ops on state-owned land; the Meeting has additionally earmarked $500 million for a plan to finance limited-equity co-ops within the Mitchell-Lama mould. (Negotiations over the state finances are anticipated to increase to Thursday.)

The guide can also be a nostalgic have a look at a vanishing Jewish New York. Whereas the comparatively various Higher West Aspect nonetheless has a big and largely liberal Jewish neighborhood, the gaps between haves and have-nots are solely rising wider and the housing inventory is out of attain to all however the prosperous.

Baum, second from left, with associates within the yard of RNA Home. There, in a “extensive open space flanking the constructing, we cycled, roller-skated, performed handball, tag, hopscotch, and double Dutch, and climbed on a space- age cement jungle fitness center.” Baum writes. (Erminio Gubert, courtesy Jennifer Baum)

Baum, 61, a filmmaker and author now dwelling in Brooklyn, remembers a funkier, much less gentrified UWS,

recognized for its Cuban-Chinese language, Kosher, Center Jap, Italian, Greek, and Irish eating places, Jewish refugees who’d escaped Hitler and pogroms, stoned junkies, muggings, the deinstitutionalized mentally ailing dwelling in single-room occupancy motels (SROs), artwork movie aficionados on the Thalia, Cuban musicians, artists, actors, crooks, prostitutes, political activists, grape boycotters, alcoholics, eccentrics, graffiti, sidewalks carpeted with damaged glass, canine shit, and litter….

If that doesn’t sound interesting, Baum additionally remembers taking part in with children from quite a lot of backgrounds — middle-class and poor, Black and white, Jewish and Puerto Rican. Cautious of showing Pollyannaish, when she started researching the guide she reached out to members of the “Developing Up on the Previous Higher West Aspect” Fb group. Positive sufficient, they too shared reminiscences of a neighborhood the place folks bought alongside throughout racial and sophistication strains and, particularly within the Mitchell-Lama homes, shared a way of frequent goal and cooperation that turned town right into a type of village.

“I used to be dwelling in Vancouver when a pal wished me to go to some type of racism workshop, and I stated to her, ‘You realize, my entire life has been a racism workshop,’” Baum recalled. “I really feel very lucky to have grown up simply the best way I did and I credit score that to my dad and mom.”

Her mom Judy, who would later grow to be an advocate for New York Metropolis’s public colleges, was from Brooklyn; her father Charles was from the Bronx. Her paternal grandmother was born on the Decrease East Aspect and labored, like so many Jews on the time, in a garment manufacturing facility. “She adored Eleanor Roosevelt,” recalled Baum, who relates how the president’s spouse gave a speech in 1935 when the New York Metropolis Housing Authority constructed the primary federally funded public housing venture. “She spoke about how necessary it was for the federal government to take accountability for folks.”

Her dad and mom weren’t radicals, however progressives who got here of age within the Nineteen Fifties and believed “within the dream of equality via structure,” Baum writes. As “cooperators”at RNA Home, she explains, they owned a share of the co-op, which they needed to promote again for a similar quantity in the event that they left. Members of the family couldn’t inherit the property until they lived there full time; when the cooperators offered or died, a brand new household would take over, plucked from a protracted ready record. RNA Home additionally included residences with lowered upkeep prices for neighbors displaced by growth.

Help the New York Jewish Week

Our nonprofit newsroom will depend on readers such as you. Make a donation now to assist unbiased Jewish journalism in New York.

“The concept was to not make a revenue however to stay an inexpensive, secure, communal life in an built-in neighborhood during which everyone had a stake,” writes Baum.

Jennifer Baum writes concerning the historical past of inexpensive housing in New York Metropolis in her hybrid memoir, “Simply Metropolis.” “With a view to protect town’s distinctive character and halt housing inequality,” she writes, “town should construct and preserve inexpensive housing on a grand scale.” (Fordham College Press)

Baum’s father, a professor turned mechanical engineer, died when she was 10 — shockingly, throughout a go to to her elementary college. Judy Baum would stay at #14E till her dying, at 77, in 2013. Her daughters’ grief was compounded by the fact of getting to relinquish the condo, which Baum describes in a chapter that plumbs the dilemmas of the sponsored co-op mannequin.

“It was devastating and I nonetheless really feel devastated by it,” Baum instructed me. “It wasn’t a lot that I wished to carry on to it as a result of I wished to show a revenue and make $3 million. It was that this condo meant a lot to me emotionally. I knew that it ought to stay public as a result of it’s solely truthful. And I wished to carry on to it as a result of it had such emotional worth to it. I nonetheless have a tough time strolling by RNA.”

Writing about latest efforts to denationalise RNA Home, Baum describes how these tensions are magnified not simply by greed however by rational human calculations. Residents seeing residences in privatized buildings promoting for seven figures are understandably chagrined to surrender their very own residences in return for “fairness accrued minus repairs” — in Baum’s case, $34,000 in 2014, when a typical three-bedroom in Manhattan was promoting for $1.5 million. Black residents whose households had been subjected to redlining understandably resent having to forgo a revenue from one more property during which they’ve invested years of their lives.

Baum’s previous pal Mondello Browner, who grew up in an enormous Mitchell-Lama growth in Central Harlem and now analyzes housing information for town, described his personal ambivalence to her:

I very a lot need Mitchell-Lamas to stay viable decisions for middle-class residents. I do understand that many long-term residents want to be rewarded for his or her persistence and longevity with the flexibility to promote out, or I suppose to get house fairness loans, primarily based upon market-rate values. However this capacity is on the expense of the present crop of financially struggling, aspiring people who’ve one much less set of financial ladders to make use of.

To this point, cooperators at RNA Home haven’t voted to denationalise, though, between 1989 and 2017, “practically 20,000 of the city-supervised co-ops and leases in Mitchell-Lama buildings have left this system,” in keeping with town.

Though Baum writes about different ethnic teams and the racial inequities constructed into some metropolis housing applications, hers can also be a strikingly Jewish story. Jews like her dad and mom — “pink diaper” progressives, as one in all her interviewees described them — had been significantly drawn to Mitchell-Lama co-ops, whereas others chased the American Dream to Lengthy Island and Westchester County.

Baum writes that the lounge of her household’s condo at RNA home “was small however nonetheless sufficiently big for teak shelving models, a console with a turntable and receiver, a liquor cupboard, a winged chair with a footstool, a brown couch with slanted arms and tapered hairpin legs, and an inherited child grand piano.” (Courtesy Jennifer Baum)

It’s a conflict of values — political and financial — that Baum captures in a reference to “Marjorie Morningstar,” Herman Wouk’s mid-century novel a few striving Jewish household.

Within the novel, Marjorie’s Jewish dad and mom transfer to a ritzy constructing on Central Park West. “By shifting to the El Dorado,” writes Wouk, “her dad and mom had carried out a lot, Marjorie believed, to make up for his or her immigrant origin.” For Baum, these had been the “reverse objectives of my progressive dad and mom, who strove for social justice, not social success.”

Jews are additionally overrepresented among the many powerbrokers who formed housing in New York within the twentieth century. Baum writes of the Jewish-led unions that constructed cooperative housing and middle-income leases. Her heroes embrace liberals like New York Mayor Fiorello La Guardia and Manhattan Borough President Ruth Messinger; her villains embrace grasp planner Robert Moses and Mayor Mike Bloomberg. Baum blames Bloomberg and one other former mayor, Rudy Giuliani, for placing the pursuits of personal builders and the wealthy forward of the “frequent good.”

I requested Baum if she empathized with those that are grateful to Giuliani and Bloomberg for making town safer, cleaner and extra financially solvent, even when gentrification got here on the expense of a extra vibrant road life and the sorts of mom-and-pop shops that she remembers so fondly.

Help the New York Jewish Week

Our nonprofit newsroom will depend on readers such as you. Make a donation now to assist unbiased Jewish journalism in New York.

“I really feel it shouldn’t be a tradeoff. I don’t really feel prefer it ought to be cleaner and extra livable for the wealthy folks. It’s simply not truthful,” she stated. “We should always be capable of have clear livability for everyone. I used to assume that the Mitchell-Lamas within the neighborhood paved the best way for inevitable gentrification. It didn’t should be that means: The federal government might have continued to construct inexpensive housing even because the neighborhood turned safer.

“It shouldn’t be an both/or scenario.”

is editor at giant of the New York Jewish Week and managing editor for Concepts for the Jewish Telegraphic Company.

The views and opinions expressed on this article are these of the writer and don’t essentially mirror the views of NYJW or its mum or dad firm, 70 Faces Media.

[ad_2]

Source link