[ad_1]

AMHERST, Massachusetts (JTA) — Since its opening in 1997, the Yiddish Ebook Heart has wowed guests with its structure. A Jewish village resurrected on a school campus in sylvan Amherst, Massachusetts, the constructing conveys the Heart’s mission: to rescue and revive a language spoken for over 1,000 years by Ashkenazi Jews in German-speaking lands, Japanese Europe and wherever they migrated.

On Oct. 15, the Heart is unveiling a brand new core exhibit, meant to flesh out and deepen the story informed by its constructing and the treasures saved inside. Arriving at a second when Yiddish is experiencing considered one of its periodic revivals, “Yiddish: A International Tradition” is a significant Yiddish establishment’s reply to a query with out straightforward solutions: How do you inform the story of a language with out a nation, and of a tradition that misplaced a majority of its purveyors in a bit over a decade of insanity?

In response, the brand new exhibit depicts the “secular” Yiddish tradition that arose within the mid-Nineteenth century as a distinctly transglobal, fashionable motion that features theater, the press, mass market publishing and mental ferment in huge cities from Warsaw to New York to Shanghai.

The exhibit is “foregrounding a narrative of creativity, super accomplishment and super range of a tradition that has migration constructed into its DNA,” David Mazower, the Heart’s analysis bibliographer and the exhibition’s chief curator, informed me once I visited Amherst final month.

The shows within the exhibit will encompass and weave out and in of the Heart’s e-book stacks, one other hanging architectural characteristic of the constructing. The stacks provide duplicates of the Heart’s assortment of 1.5 million Yiddish books and periodicals, on the market and shopping. I couldn’t be the primary customer to be reminded of the closing scene in “Raiders of the Misplaced Ark,” which reveals a colossal authorities warehouse stuffed with, within the phrases of the screenplay, “crates and crates. All trying alike. All gathering mud.”

What an informal customer won’t see is all that’s occurring on the Heart to blow the mud off these books, together with translator workshops, summer time fellowships, conferences, an oral historical past undertaking, a busy publishing program and a riotous summer time music competition.

Curiosity in all of these actions has been helped alongside by younger Jews within the language and tradition and a pandemic that created a requirement for on-line Yiddish courses. The Yiddish Ebook Heart has been drawing 10,000 guests a 12 months since its pandemic shutdown. The New York Instances made the newest revival official (to non-readers of the Jewish media, anyway) in an essay final month by the Jewish polymath Ilan Stavans, declaring that “Yiddish Is Having a Second.” Stavans notes a flurry of new translations of obscure and traditional Yiddish writers, the all-Yiddish staging of “Fiddler on the Roof” and the Yiddish dialogue in three latest Netflix collection: “Shtisel,” “Unorthodox” and “Tough Diamonds.”

A mural that includes key moments within the international historical past of Yiddish is a central characteristic of a brand new core exhibit on the Yiddish Ebook Heart in Amherst, Massachusetts. (JTA picture)

(Extra controversially, Stavans additionally stories that Yiddish is interesting to these — presumably younger anti-Zionist Jews — for whom Hebrew “symbolizes far-right Israeli militarism.”)

Such a revival additionally challenges keepers of the flame — not simply the Yiddish Ebook Heart, however the YIVO Institute for Jewish Analysis in New York, The Staff Circle, publications like In geveb and the Yiddish Ahead, educational departments plus a number of regional Yiddish organizations — to outline a language and tradition meaning many various issues to many various individuals.

Is it a language of a decimated previous? A progenitor of the Jewish left? A tongue, nonetheless spoken each day by haredi Orthodox Jews, that continues to develop and evolve? Is it an angle — a Jewish method of being and considering — that survives in humor and cooking and music even when those that admire it will probably’t converse the language? For European Jews of the Enlightenment, the Yiddish scholar Jeffrey Shandler jogged my memory a couple of years in the past, “Yiddish represented the resistance and incapability of Jews to enter the cultural mainstream. It represented one thing atavistic, a method of holding Jews again.” For Zionists, in the meantime, it represented a weak Diaspora and all the pieces related to it (a conflict explored in a present YIVO exhibit, “Palestinian Yiddish: A Have a look at Yiddish within the Land of Israel Earlier than 1948”).

Goldie Morgenthaler, herself the daughter of the Yiddish author Chava Rosenfarb, has written that she teaches Yiddish literature to principally non-Jewish college college students in Alberta, Canada as a result of “finding out what is particular to 1 tradition is commonly step one to understanding many cultures.”

At YIVO, an establishment based by students in Vilna in 1925 and transplanted to New York in 1940, Yiddish is considered an expression of and automobile for “Jewish satisfaction,” in keeping with its government director and CEO, Jonathan Brent.

“For Jewish individuals within the Diaspora to know that they’ve in truth a future as Jews,” he stated final week, “they must take satisfaction of their heritage. For every kind of historic causes, many Jews felt that [Yiddish] was someway a shameful or devalued heritage. It was ‘zhargon’ [jargon], and it had been principally eradicated from public discourse within the land of Israel. YIVO from the very starting needed to review Yiddish as a language amongst languages, the identical method you studied Russian or Spanish or French. It was a language with a historical past.

David Mazower, the Yiddish Ebook Heart’s analysis bibliographer and the exhibition’s chief curator, reveals off a samovar for use in a recreation of the Warsaw literary salon of author I.L. Peretz. (JTA picture)

“What Yiddish does,” he continued, “is assist anchor us within the language during which our grandparents and nice grandparents communicated their deepest ideas and emotions. And that has actual implications for the survival of the Jewish individuals.”

Aaron Lansky, the founder and president of the Yiddish Ebook Heart, stated the story he desires to inform goes again to his days as a graduate scholar in Yiddish at McGill College within the Nineteen Seventies, when he first began saving the discarded books that may turn out to be the core of the Heart’s assortment.

“Folks consider [Yiddish] as this nostalgic creation,” he stated. “However the fact is, it was a profound, multifaceted and actually international literature that emerged within the late 19th century, after which simply took off all through the 20th century…. It wasn’t lengthy earlier than writers have been utilizing each type of literary expression — expressionism, impressionism, surrealism, eroticism. All of it discovered expression on this very quick time period, and even the Holocaust didn’t destroy it. “

Lansky admits his personal imaginative and prescient is extra literary than the core exhibit’s, and thanked Mazower for making a broader view of Yiddish as a world tradition.

That view is represented in a 60-foot mural that serves as an introduction to the exhibit. Cartoons by the German illustrator Martin Haake depict key historic vignettes in Yiddish historical past, from practically each continent. Glikl of Hameln, a German-Jewish businesswoman, writes her diaries on the flip of the 18th century. Girls name for a strike at “Yanovsky’s Cigarette Manufacturing facility” in Bialystok, Poland, in 1901. A nursery scene honors the main Yiddish activists who have been born in Displaced Individuals camps after World Struggle II. And tubercular Yiddish writers are seen recovering on the Jewish Consumptive Reduction Society in Denver, Colorado, which operated from 1904 to 1940.

The mural strains the ramp that results in the bookshelves, the place shows (a few of which Mazower calls “wedges”) use artifacts and wall-mounted photographs to speak concerning the breadth of Yiddish tradition. There’s a show about Yiddish celebrities, together with writers, corresponding to Sholom Aleichem and Chaim Zhitlowsky, who would draw tens of hundreds of mourners to their funerals. One other show honors those that preserved and studied Yiddish tradition, from YIVO (described right here as “The Mothership”) to the monumental “Language and Cultural Atlas of Ashkenazic Jewry” undertaken between 1959 and 1972 by the linguist Uriel Weinreich. A Yiddish linotype machine, rescued by Lansky, anchors an exhibit concerning the Jewish press.

Michal Michalesko (heart) and refrain seem in a publicity picture from an unidentified manufacturing, ca. 1930. Michalesko (1884–1957) made his title within the 1910s as a star of the Warsaw Yiddish operetta stage. (Yiddish Ebook Heart)

A centerpiece of the core exhibit is a recreation of the Warsaw literary salon of the author and playwright I.L. Peretz, a number one determine of the late Nineteenth century and early twentieth centuries. Whereas few precise artifacts belonging to Peretz survive, the room will embrace contemporaneous objects and images to immerse guests within the literary scene of the day.

“You’ll step by way of his doorway the way in which that so many younger writers did, clutching their first manuscripts to point out them both in Hebrew or in Yiddish,” Mazower defined. “His title, his handle was identified all through the Russian Empire at the moment. Folks would come hundreds of miles in some circumstances to Warsaw to attempt to get entry into this alchemy-like area the place extraordinary issues occur.”

A kind of pilgrims was Mazower’s great-grandfather, the famed playwright Sholem Asch. When Asch confirmed Peretz a draft of his infamous play “God of Vengeance,” whose lesbian subplot would shock audiences and rile spiritual leaders, Peretz reportedly informed him to burn it.

“My hope is that by way of the exhibition as an entire you see Jewish historical past by way of a Yiddish lens and otherwise from the Holocaust-defined story that so many people have been educated with and that well-liked tradition feeds us,” stated Mazower.

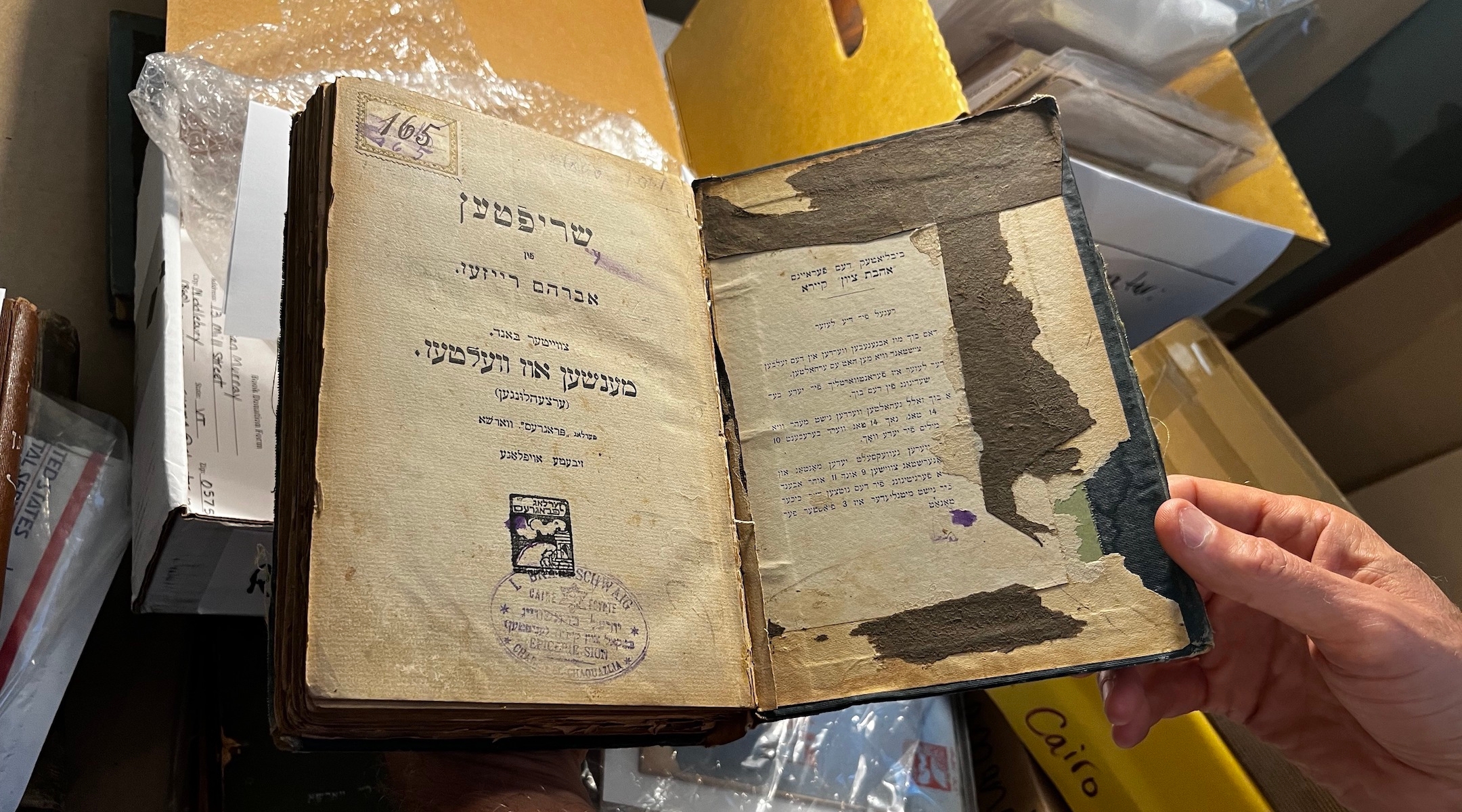

A Yiddish e-book includes a stamp for a bookseller in Cairo, demonstrating the worldwide attain of the language. (JTA picture)

The exhibit treats the Holocaust as one a part of the Yiddish story, not its fruits. The unique Yiddish version of Elie Wiesel’s “Evening,” revealed as a part of a memorial undertaking in Argentina shortly after the struggle, rests in a wedge about people who rescued Yiddish tradition below the Nazis. The identical part includes a tribute to Rokhl Brokhes, a author murdered within the Minsk Ghetto in 1945. A nonetheless from a latest animated adaptation of considered one of her tales by Alona Bach, at present a PhD scholar at MIT specializing in the “intersections of electrical energy and Yiddish,” affirms one of many Heart’s goals: to convey younger Yiddishists into dialog with the previous.

The story of Yiddish theater will wrap across the auditorium, beginning with a big picture of the viewers on the opening of the Grand Avenue Theatre in New York in 1905. A memorial part remembers the most likely hundreds of actors, playwrights and musicians who have been killed within the Holocaust.

“Had Yiddish theater not suffered a rupture, which it did, it will have continued to evolve and borrow and develop,” stated Lisa Newman, the Heart’s director of publishing and public packages. “What’s so essential about this exhibition is that it locations Yiddish on this context of language at least another nation’s, besides it’s not a rustic.”

I requested Mazower what sort of tales he didn’t wish to inform about Yiddish tradition.

“It’s not a narrative about Yiddish humor,” he stated. “It’s not a narrative concerning the Holocaust. It’s not a narrative concerning the state of Israel. It’s not a lachrymose story about Jewish persecution by way of the ages.”

Different Yiddishists informed me a lot the identical factor (Brent stated that the story of Yiddish “shouldn’t be informed as a group of jokes, or Yiddish curses, or as a cute language that connects you to Bubbe’s gefilte fish”).

And but, stated Lansky, “We’re not feinschmeckers, we’re not elitist on the subject of Yiddish. Yiddish was a vernacular language, and I’m pleased to embrace that. I like the humor and social criticism that’s embedded in it. It’s the mixture that’s so spectacular. To see all of this literature and tradition in a energetic and accessible method may be fairly transformative.”

[ad_2]

Source link