[ad_1]

(JTA) — My mother and father, youngsters of Japanese European Jewish immigrants, have been named Irving and Naomi. They named their three sons Stephen, Jeffrey and Andrew. My children’ names are Noah, Elie and Kayla.

Our first names seize the sweep of the American Jewish expertise, from the early twentieth century to the early twenty first. At every cease on the journey, children got names — typically “Jewish,” typically not — that inform you one thing about how they match each into Jewish custom and the American mosaic.

A brand new research from the Jewish Language Undertaking at Hebrew Union School-Jewish Institute of Faith charts how Jewish names have advanced over that historical past and what they are saying about American Jewish identification. For “American Jewish Private Names,” Sarah Bunin Benor and Alicia B. Chandler surveyed over 11,000 individuals who recognized as Jewish, asking in regards to the names they got and the names they have been giving their youngsters. (Additionally they consulted a number of databases, together with the indispensable Jewish Child Names finder from my colleagues at Kveller.)

The outcomes recommend my household’s first names have been typical: Within the century since my grandparents (Albert, Sarah, Sam and Bessie) arrived at Ellis Island, and after an period of Susans and Scotts, American Jews grew to become increasingly probably to provide their youngsters Biblical, Hebrew, Israeli and even ambiguous names which have come to sound “Jewish.” “The highest 10 names for Jewish ladies and boys in every decade replicate these adjustments,” the authors write, “comparable to Ellen and Robert within the Fifties, Rebecca and Joshua within the Seventies, and Noa and Ari within the 2010s.”

It’s a narrative about acculturation, say the authors, but in addition about distinctiveness: As soon as they felt totally at residence, Jews asserted themselves by choosing names that proudly asserted their Jewishness.

On Thursday, I spoke with Benor, vice provost at HUC-JIR in Los Angeles, professor of latest Jewish research and linguistics and director of the Jewish Language Undertaking. Our dialog touched on, amongst different issues, at present’s hottest Jewish names, the Jewish names folks give to their pets and the aliases many individuals give to Starbucks baristas. Principally we spoke in regards to the methods Jewish custom and American innovation are expressed in our first names.

This interview was condensed and edited for readability

Jewish Telegraphic Company: I wish to begin with the massive takeaway out of your research: “Youthful Jews are considerably extra probably than older Jews to have Distinctively Jewish names.” Does that sound correct?

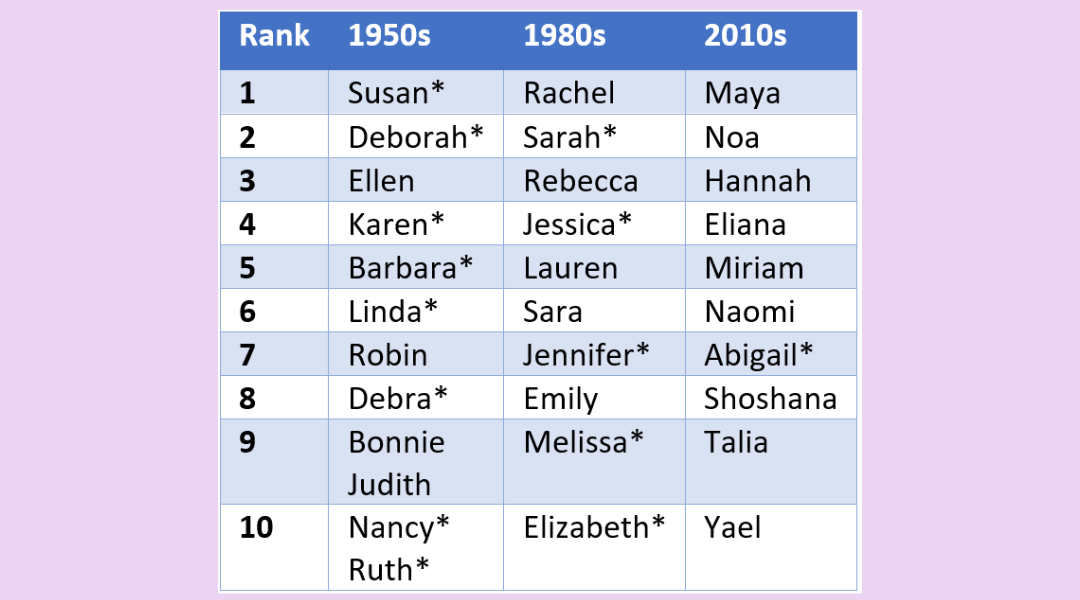

Sarah Bunim Benor: Undoubtedly. The factor that I believe individuals are going to be most enthusiastic about is the chart displaying the preferred names by decade. Should you take a look at the Fifties, you may have ladies’ names like Barbara, Linda and Robin. These will not be distinctively Jewish and never biblical. After which by the Nineteen Eighties, it’s very biblical: Sarah, Rachel, Rebecca. By the 2000s the highest three names are Hannah, Maya and Miriam. And by the 2010s you get these names which are both biblical or fashionable Hebrew or coded Hebrew: Noa, Eliana, Naomi.

Prime 10 ladies’ names amongst Jewish respondents to the “Survey of American Jewish Private Names,” by a long time of start. (An * signifies that the identify can be within the total U.S. Prime 10 for that decade.) (www.jewishlanguages.org)

You notice that at present many of the high 20 Jewish ladies’ and boys’ names are English variations of Biblical names. However that doesn’t account for all of the “Jewish” names within the research, which vary from “Hebrew Publish-Biblical,” like Akiva, Bruria and Meir, to the “ambiguously Jewish,” like Lila and Mindy. How did you resolve which names are distinctively Jewish?

We primarily based our judgment on our respondents’ judgments. We had them fee their very own names, and ask, Should you met somebody together with your identify, how probably would you assume that they have been Jewish on a scale of zero to 10? And we had them do the identical for a pattern of, I believe it was 13 male names and 13 feminine names.

By which you found that there are presently “names of no Jewish origin” which have come to be seen as Jewish.

Undoubtedly. And those that I discover most fascinating in that class are the coded Jewish names like Maya and Lila and Eliana, and different names which are standard in America, like Emmett. They’ve these coded Jewish meanings. [“Maya” is thought to relate to mayim, the Hebrew word for water; in Hebrew, “lilah” means “night” and “emet” means “truth.”] And Evan [“rock” in Hebrew and “John” in Welch] is one other instance the place we American Jews interpret these American names as Jewish names as a result of they’ve homologous interpretations in Hebrew.

Eliana, for instance, is just not of Jewish origin, but it surely sounds precisely like “li ana,” my God answered. And so it’s a phenomenal identify. And it’s develop into fairly standard amongst Jews.

I take into consideration my father’s technology — the technology of Irvings and Stanleys and Sylvias. They usually grew to become distinctively Jewish names with out being Jewish names, proper? Was that about folks eager to assimilate, but in addition not eager to disappear into the mainstream?

When immigrant mother and father gave their youngsters names like Irving and Stanley, it was an try to Americanize, but in addition they selected names that their neighbors or buddies have been giving their infants, and so it ended up that some names turned out to be seen as Jewish names.

I’m simply making an attempt to assume what was inside my grandmother’s head when she named my father Irving — maybe she wished the kid to sound like an American however not essentially like a gentile.

She won’t have considered it as sounding like a gentile identify. She may need considered it as sounding like an American Jewish identify.

You in contrast the names of your respondents and the names of their youngsters. What does this inform us about naming developments?

Throughout generations, teams elevated of their Jewish distinctiveness over time. Take, for instance, names we categorize as “of no Jewish origin,” like Richard and Jennifer. There’s a important drop between the older technology and the youthful technology with regards to such names.

Which means the Richards and Jennifers will not be naming their children Ellen and Steven however Maya and Ezra.

Sure. Though there are nonetheless many Jews who do use names of no Jewish origin, it’s a lot lower than it was earlier than.

We now have information on identify altering, and I used to be shocked at how few folks reported altering their identify to 1 that sounds much less Jewish. The identify adjustments that we heard have been extra about adjustments in gender presentation and adjustments for numerous different causes however to not sound much less Jewish.

You talked about 1970 as a form of pivot level, through which a decline in Jews altering their final names is changed by a rise in child names thought-about extra Jewish. Remind us of that historical past.

There’s a fantastic guide about this, “A Rosenberg by Any Different Identify,” by Kirsten Fermaglich. She discovered that Jews in the course of the twentieth century have been altering their names — due to antisemitism, as a result of they weren’t capable of get into universities or keep at accommodations or get sure jobs due to their names. It was a manner of integrating into American society, not essentially as a manner of assimilating. Simply because they modified their names didn’t imply that they have been not recognized with Jewish communities. They tended to nonetheless be engaged.

After which within the ‘60s and ‘70s, it grew to become extra acceptable to have a particular ethnic identification. Antisemitism diminished considerably, but it surely was additionally a part of a broader American pattern to focus on your ethnic distinctiveness. Jews participated in that in quite a few methods, together with a bent to provide their infants distinctive names.

That theme runs by way of your dialogue: the backwards and forwards between acculturation and distinctiveness.

That has been the case all through Jewish historical past. Wherever Jews have lived, they’ve needed to provide you with a steadiness between acculturation and distinctiveness, and in some circumstances, it was rather more on the acculturation aspect. In some circumstances, it was rather more on the distinctive aspect.

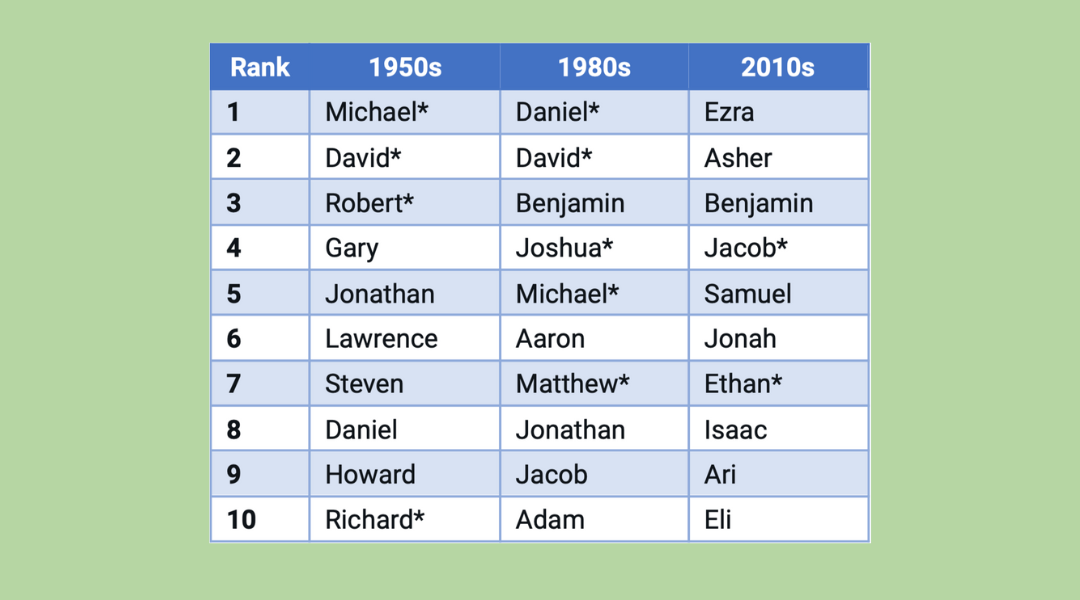

Prime 10 boys’ names amongst Jewish respondents to the “Survey of American Jewish Private Names,” by a long time of start. (An * signifies that the identify can be within the total U.S. Prime 10 for that decade.) (www.jewishlanguages.org)

You describe how the distinctiveness of Jewish child names rises with the mother and father’ engagement in Jewish life, together with visits to Israel, synagogue attendance, denomination. You additionally notice that “rabbis and cantors have the best charges of kids with Distinctively Jewish names, adopted by Jewish educators and Jewish research students,” and that Orthodox Jews are extra probably than non-Orthodox Jews to select names excessive on the size of Jewishness. Let’s speak about how these developments improve throughout ranges of engagement.

One other actually hanging picture to me is the time spent in Israel. Having a distinctively Jewish identify and particularly having a contemporary Hebrew identify improve with how a lot time the mother and father have spent in Israel. And also you get related spreads for different issues like denominations. One thing like 69% of haredi or “black-hat” Jews give their youngsters distinctively Jewish names, in comparison with 35% of Fashionable Orthodox. So there’s a large cut up even among the many Orthodox. After which you already know, for different denominations, it’s even decrease than that.

I used to be shocked how many individuals nonetheless have Jewish ritual names along with their given “English” names — in my case, I’m Avrum on my marriage ceremony contract and when referred to as up for synagogue honors. Wasn’t it over 90%?

Sure, 95% of the respondents say they’ve a ritual identify, however lots of these are the identical identify as their non-ritual identify, like “Sarah.” That does replicate our pattern being extra engaged in Jewish life than the typical random pattern of Jews. What’s fascinating right here is the Orthodox versus non-Orthodox youngsters, the place 64% of Orthodox youngsters have precisely the identical ritual identify as their given first identify, which signifies that they’re giving their youngsters distinctively Jewish names, and non-Orthodox youngsters solely 30%.

The ritual names conference, which for a very long time was reserved for boys, opens up a complete dialogue of gender — together with the truth that there are simply so many extra male biblical names than feminine names.

Should you take a look at the names which are hottest amongst Jewish respondents by decade of start, you see that the women’ names embrace some fashionable Hebrew names that aren’t biblical, like Talia and Noa, and that among the many hottest male names from the 2010s, the names are nearly all biblical names.

You additionally speak about Sephardi/Mizrahi and Ashkenazi naming conventions, which I believe most individuals affiliate with the concept that Ashkenazim don’t identify a baby after a dwelling relative. Your survey confirms that that custom is holding fairly robust.

To some extent, though I used to be sort of shocked what number of Sephardi respondents completely named youngsters in honor of deceased kinfolk — like 40% or extra of those that establish as solely Sephardi or Mizrahi. They’ve the best fee of naming after dwelling honorees, however additionally they have the best fee of naming after no honorees. Granted, our pattern of Sephardic and Mizrahi Jews is fairly small, regardless of our efforts to get respondents who aren’t Ashkenazi.

The research discusses “Starbucks names.” Is {that a} time period of artwork within the social sciences?

It refers back to the concept of a reputation that you simply use for some service encounters [such as buying coffee] that’s completely different from your personal, as a result of your personal identify is difficult to spell otherwise you don’t wish to hear your identify referred to as in a public place. I discovered that Jews with distinctively Jewish names have been more likely to make use of a Starbucks identify typically than those that don’t have distinctively Jewish names. However I used to be additionally shocked that some individuals who don’t have distinctively Jewish names additionally use a Starbucks various that’s extra Jewish as a result of they wish to establish in public as Jewish.

After which there’s the Aroma identify, named after the Israeli espresso chain. That’s the place Individuals give a Hebrew spin to their English identify that they know the Israeli barista goes to mispronounce.

Yeah, precisely. That was enjoyable. I hadn’t heard that time period, however a number of the respondents use it. A Kelly stated she makes use of “Kelilah” in Israel.

Does Starbucks naming really prolong to code-switching elsewhere? I’m pondering of the technology that included folks like, say, Rabbi Irving Greenberg, who goes by “Yitz,” brief for Yitzhak. I believe that technology — Rabbi Greenberg is 89 — did code swap to a point.

That’s proper. Or Bernard Dov Spolsky [a professor emeritus in linguistics at Bar-Ilan University], who handed away two weeks in the past. He was from New Zealand and his English identify was Bernard and he printed underneath Bernard Spolsky, however he glided by Dov in Jewish circles.

What’s the significance of finding out names? What do they reveal in regards to the neighborhood?

Names are such an vital a part of how we current ourselves to the world. Folks spend months earlier than they offer start or undertake their little one developing with a listing of names and the way they wish to characterize themselves and sometimes how Jewishly they wish to characterize themselves. And other people additionally typically take into consideration their names later in life. Do they wish to go by the identify they got or go by a nickname? Or do they wish to utterly change their identify?

Whenever you take a look at this information set, what does it inform you about American Jewry at this second?

There are two methods to reply that. One is thru the acculturation and distinctiveness lens. I believe the information present that Jews have develop into extra distinct over time within the final 60 or 70 years or so. You can even look by way of the lens of custom and innovation. Are American Jews utilizing naming practices which were components of Jewish communities for hundreds of years, or are they developing with new traditions? A lot of the naming practices replicate traditions which were a part of Jewish communities for hundreds of years, with some fashionable spins. Even the Starbucks identify: When Hadassah goes by Esther within the Purim story, you may consider that as a historic Starbucks identify.

And pet names: You discovered that 32%, a large minority, of Jewish pet house owners give their pets names they think about Jewish, like Latke or Feivel or Ketsele.

I don’t know if Jews traditionally used Jewish names for his or her pets. I don’t know of any research of that. However the truth that that’s such a standard factor amongst modern American Jews could replicate the significance of pets in our tradition, but in addition the will of Jews to focus on their Jewishness, even when their youngsters don’t have distinctively Jewish names. That’s one other manner that they’ll current themselves to the world as Jewish.

is editor in chief of the New York Jewish Week and senior editor of the Jewish Telegraphic Company. He beforehand served as JTA’s editor in chief and as editor in chief and CEO of the New Jersey Jewish Information. @SilowCarroll

The views and opinions expressed on this article are these of the writer and don’t essentially replicate the views of JTA or its dad or mum firm, 70 Faces Media.

[ad_2]

Source link