[ad_1]

LONDON — They didn’t understand it, nevertheless it was the eve of the Passover seder. At 2:00 p.m. on April 7, 1944, 19-year-old Rudolf Vrba and 25-year-old Fred Wetzler started their epic and daring bid to carry the information of the horrors of Auschwitz to their fellow Jews and the broader world.

That bid started in a darkish, cramped gap below a woodpile within the loss of life camp. It ended with a report describing the Nazi equipment of slaughter which landed on desks in Allied capitals and, by a collection of diplomatic maneuvers, helped to avoid wasting the lives of as much as 200,000 Jews in Budapest.

However, for greater than seven many years, the story of Vrba and Wetzler’s astonishing escape — the primary profitable effort by Jewish prisoners to interrupt out of Auschwitz — and their mission to sound the alarm and strip away the layers of deception below which the Remaining Answer was perpetrated has itself remained considerably hidden. The popularity they rightly deserve has consequently been denied.

In his newly printed e-book “The Escape Artist,” British author and journalist Jonathan Freedland seeks to appropriate this historic injustice, painstakingly however grippingly reconstructing Vrba’s unbelievable life.

Freedland, a columnist for The Guardian newspaper and host of a preferred BBC radio historical past program, tells The Occasions of Israel that his purpose is to make sure that Vrba has, ultimately, “a spot within the pantheon of heroes of the Holocaust.”

And, says Freedland, this isn’t merely a narrative concerning the previous. Vrba’s perception concerning the potential energy of shining a light-weight onto Auschwitz’s darkish secrets and techniques holds salutary classes for our “post-truth age.”

Strive, attempt once more

Walter Rosenberg — the identify Vrba was given to him as a canopy after his escape from Auschwitz — was born in western Slovakia in 1924. A precocious baby with a present for languages and arithmetic, he was compelled out of college at 14 when Slovakia’s puppet regime, established following Hitler’s 1939 dismemberment of Czechoslovakia, launched a collection of antisemitic laws.

When, in February 1942, Vrba was ordered to report for “resettlement,” his quick thought was to flee to England to affix the Czechoslovak military in exile. Whereas he didn’t succeed, {the teenager} managed to make it to Budapest the place he made contact with the underground. Finally, after being roughed up by Hungarian troops, he ended up again within the arms of the Slovaks who despatched him to the Nováky detention camp.

Nonetheless, Vrba’s willpower to flee had on no account diminished. Certainly, he managed to slide out of Nováky with Josef Knapp, a younger man from his birthplace. His subsequent betrayal by Knapp, which led to Vrba being returned to the camp, taught the 17-year-old an necessary lesson that helped him to outlive what lay forward: belief no one.

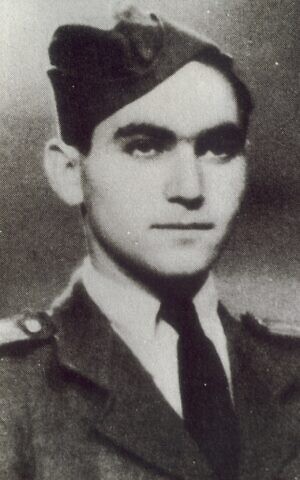

Rudolf Vrba in navy uniform on this undated photograph. (Courtesy of Robin Vrba)

When he was transported to Auschwitz in June 1942, Vrba quickly realized that ideas of escape needed to be subordinated to the calls for of merely staying alive. If mistrust was one consider Vrba’s survival, luck was one other. Despatched to IG Farben’s brutal Buna manufacturing facility, he was recruited by a French civilian to do much less onerous work. He was later transferred from the infamous gravel pits to a job portray skis for troops on the Japanese Entrance. And, after being chosen for execution throughout an August 1942 typhus outbreak by which 746 males had been murdered, he was saved by a kapo.

Maybe Vrba’s best stroke of luck, nevertheless, was being despatched to work in “Kanada,” a unit that sorted by the belongings of latest arrivals at Auschwitz. The work included ferrying luggage and rummaging by valuables, together with squeezing tubes of toothpaste probably containing diamonds or money that had been stashed away. Crucially, nevertheless, the prisoners had been additionally in a position to surreptitiously steal meals that newly arrived prisoners had introduced with them to the camp. The newcomers had been, by this level, possible already lifeless.

Vrba’s time in Kanada slowly led him to a surprising realization: that Auschwitz was, as Freedland places it, not merely a slave labor or focus camp, however “a manufacturing facility of loss of life.” He additionally got here to the sickening understanding that something of worth present in Kanada was shipped on trains again to Germany: The Nazis had been trying to show a revenue on their coverage of mass homicide.

Deception introduced loss of life

Vrba’s switch to work on the “ramp” — the place he spent 10 months serving to to take away the bags of latest arrivals and filter the cattle vehicles — led him to understand a closing fact concerning the mechanics of this manufacturing facility of loss of life: that deception was essential to its easy functioning. Unaware of their destiny, the deportees largely obeyed the Nazis’ directions — inadvertently making certain the order the SS required to commit industrial-scale homicide. If the wheels of the killing machine had been to be slowed, Vrba believed, this veil of secrecy needed to be lifted and Jews wanted to be forewarned of their imminent destiny.

Jews present process choice on the ramp at Auschwitz in 1944. Seen within the background is the well-known entrance to the camp. Some veteran inmates are serving to the newcomers. (Public Area)

His close-up information concerning the expertise of the “household camp” — the place, in one other act of Nazi deceit, teams of Czech Jews had been stored in comparatively good situations ought to the Purple Cross select to go to — led Vrba to revise his perception concerning the significance of knowledge. The Czech Jews had been warned by the underground that they had been to be murdered after six months. However, nonetheless, they did nothing to withstand.

Data, Vrba got here to comprehend, needed to be accompanied by the potential for with the ability to escape the Nazi butchers. This will have been a near-impossibility in Auschwitz itself, however the door was nonetheless ajar for these Jews who had not but boarded the trains. They needed to be alerted.

For Vrba, escape thus turned a mission that was about far more than his personal survival. He sought nothing lower than to shatter the wall of lies that the Nazis had constructed — a wall that surrounded their victims at each stage of their journey to the fuel chambers.

He sought nothing lower than to shatter the wall of lies that the Nazis had constructed

Regardless of his youth, Vrba was nicely outfitted to hold out this mission. Alongside his resilience, he was gifted with robust numerical and scientific talents and an uncanny skill to retain knowledge. He additionally had what Freedland phrases an “nearly uniquely panoramic view” of Auschwitz. Except for the manufacturing facility, gravel pits, Kanada and the ramp (the place he counted and memorized particulars of the arrival choices), he additionally volunteered to work in Birkenau and, by his hyperlinks to the underground resistance, turned a registrar in a quarantine sub-section of the camp. As a clerk, he now had the chance not solely to wander extra freely round Auschwitz — committing to reminiscence its format and workings — he additionally had entry to the chief registrar’s data which contained extremely detailed details about the transports.

‘The Escape Artist,’ by Jonathan Freedland. (Courtesy)

Statistically, although, Vrba’s possibilities of escape weren’t good. No Jew had ever achieved this perilous feat. Nevertheless, he was, as Freedland notes, younger and, because of the character of the clerical work he had been doing, a lot fitter and more healthy than most inmates. In Kanada, he had additionally discovered a baby’s atlas and memorized the route from Auschwitz to the Slovak border. He additionally had invaluable mentoring from a Russian prisoner, Dmitri Volkov, who had as soon as escaped from Sachsenhausen. Among the many recommendation Volkov imparted was a vital piece of intelligence: machorka, a Soviet tobacco, soaked in petrol and dried, was the one accessible substance that would throw the camp’s tracker canines off of a human scent.

For Vrba, the clock was additionally ticking. In January 1944, he found {that a} new railway line, which ran straight to the camp crematoria, was being constructed in preparation for the arrival of Hungary’s roughly million-strong Jewish inhabitants. Hungarian Jews had hitherto been partially protected against the worst of the Remaining Answer. However that every one modified when Hitler occupied the nation in early 1944, snuffing out the final vestiges of Hungarian independence and forcing the nation’s opportunistic chief, Admiral Miklós Horthy, to nominate a Nazi sympathizer as prime minister.

A determined bid for freedom

Lower than three weeks later, Vrba launched his bid for freedom. Accompanying him was Wetzler, a younger man from his hometown with whom he had change into pleasant within the camp. The pair had been nicely acquainted with the drill when a prisoner was discovered to have escaped: For 72 hours, the camp went onto excessive alert and an intensive search was performed. However, after that time, the Nazis returned the outer camp — the place prisoners labored by day earlier than being herded again into the principle got here in a single day — to its much less stringent nighttime safety preparations. The plan was thus to cover in a makeshift bunker below the woodpile within the outer camp, then slip out below cowl of darkness as soon as the search was known as off.

Rodulf Vrba with daughter Helena and granddaughter Gerta on this undated photograph. (Courtesy of Caroline Hilton)

For 3 days and three nights, Vrba and Wetzler lay side-by-side within the dugout. Luck was as soon as once more on Vrba’s aspect. Whereas the machorka had stopped the search canines from giving them away, two guards had noticed the woodpile and begun to tug away the planks. However, when Vrba and his companion had been simply seconds away from discovery, the SS males had been distracted by a commotion elsewhere and disappeared, by no means to return. In an extra stroke of luck, because the three days got here to an finish, Vrba and Wetzler realized that the wood planks concealing them had been a lot heavier and harder to maneuver than that they had anticipated. If the SS guards hadn’t eliminated the primary few layers of planks, the 2 males would have been trapped within the pit.

Vrba’s luck continued as the lads started the 50-mile (80-kilometer) trek south, following the course of the Sola river, in the direction of Slovakia. Regardless of taking the precaution of strolling solely after darkish, that they had loads of slender escapes: they by accident stumbled upon a Hitler Youth camp; bought misplaced perilously near a subcamp at Jawiszowice; and awoke to search out themselves, not as they’d believed, in a secluded wooded grove however a public park the place SS males and their households had been having fun with the Easter vacation weekend. They had been even pursued and shot at by a patrol of German troopers.

The gambles they took — mandatory, although reckless — additionally paid off. A Polish peasant lady, believing them to be escaped Russian POWs, supplied them with shelter after they struggled to search out someplace to cover out in the future. Luckier nonetheless, 10 days into their trek, one other Polish lady allowed them to remain in her goat hut, supplied them with meals, and launched them to a person who guided the pair by the mountains to the border with Slovakia.

Making contact, saving lives

However attending to the relative security of his homeland had by no means been Vrba’s sole objective. As quickly as they crossed the border, Wetzler made contact with Slovakia’s Jewish council, the one communal group the regime nonetheless allowed to perform. The boys had been then subjected to a grueling 48-hour interview and cross-examination, each to ascertain their credibility and to file their story.

From their interviews, Oskar Krasnansky, one of many council’s most senior members, compiled a 32-page, single-spaced report, full with skilled drawings primarily based on Vrba and Wetzler’s testimonies. The doc was, Freedland writes, “bald and spare, freed from rhetorical fireplace. It gave the ground to information quite than ardour.”

Nonetheless, the report methodically detailed the horrors of Auschwitz and, crucially, the fictions deployed by the Nazis from the second the cattle truck doorways had been slammed on departure to that at which the fuel chamber doorways had been locked.

The report was bald and spare, freed from rhetorical fireplace. It gave the ground to information quite than ardour

Because of Vrba’s extraordinary reminiscence, the report supplied particulars of particular person transports and a country-by-country breakdown of the estimated loss of life toll throughout his time within the camp.

However, over Vrba’s robust objections, the report contained no warning to Hungary’s Jews that the camp was being readied for his or her destruction. Krasnansky was insistent: the doc was to file solely what had occurred, not present forecasts concerning the future.

Hungarian Jews arriving at Auschwitz in 1944. (Public Area)

Nonetheless, when two extra Jews efficiently escaped seven weeks later, Krasnansky added a seven-page addendum to the report which contained their account of the homicide of Hungarian Jews when transports started to reach from the now German-occupied nation in Could 1944.

Vrba was understandably pissed off that the warning he had been so determined to sound had clearly not reached the most recent victims of the Remaining Answer in time. However this wasn’t the complete story. Inside hours of the report’s completion, Krasnansky had personally handed the doc to Rezso Kasztner, the de facto chief of Hungarian Jewry.

In the meantime, having bought their arms on a replica of the report, the anti-Nazi resistance within the nation lobbied probably the most senior Protestant and Catholic bishops in Budapest to intercede with the federal government on the Jews’ behalf; the previous acted instantly, the latter stalled and stated it was a matter for the Pope.

Because of the energetic efforts of a Swiss-based British journalist who turned the report’s considerably dry language into attention-grabbing press releases, Vrba’s revelations started to filter out within the press, together with the New York Occasions, and on the BBC’s international providers. Vrba himself was invited to temporary a papal envoy who was visiting Slovakia.

Pressuring a regime to behave

Horthy’s regime had an extended historical past of antisemitism, however the Jews had a sympathizer near the middle of energy: the regent’s daughter-in-law. Furnished with a replica of the report by the Hungarian opposition, Countess Ilona Edelsheim Gyulai handed it to Horthy himself. The regent declared himself appalled by what he learn. He additionally quickly got here below exterior strain — from the Pope, the USA and the Swedish monarch — to cease the deportations.

Whereas the Vatican spoke in code and tried to enchantment to Horthy’s higher angels, the Roosevelt administration bluntly warned that “all these answerable for finishing up [these] type of injustices will likely be handled.” Painfully slowly, Horthy — who, as Freedland notes, was primarily motivated by private self-interest — started to say his tattered authority, ordering the deportations to cease and irritating Adolf Eichmann’s impending plan to ship Budapest’s 200,000 Jews to Auschwitz.

Miklos Horthy and Adolf Hitler in 1938. (Wikimedia commons/ Mareček2000/ CC BY-SA)

For over 400,000 Jews who lived in rural Hungary it was, in fact, too late. And, when the Nazis lastly ousted Horthy within the autumn, the Arrow Cross launched a reign of terror by which 1000’s of the capital’s Jews had been murdered. However Vrba had received sufficient time to make sure that, when the conflict ended, over 200,000 Hungarian Jews are believed to have survived.

However the feeling that extra might — and may — have been carried out would hang-out Vrba for the remainder of his life. He would, as an illustration, by no means forgive the truth that, as a part of Kasztner’s controversial take care of the Germans which secured exit permits for round 1,700 Hungarian Jews, Kasztner agreed to maintain silent about what he and the small management group surrounding him had realized from Vrba’s report. Kasztner thus gave Eichmann and the SS, writes Freedland, “the one factor they deemed indispensable for his or her work… order and quiet.”

Inaction by the Allies

Then there’s the query of how the Allies responded to the report. The report reached London speedily and was learn by Churchill, who instantly agreed to a request, handed on by International Secretary Anthony Eden, that the railway line between Budapest and Auschwitz must be bombed. However, as soon as handed down the chain of command, navy objections had been raised as to the feasibility of such a raid.

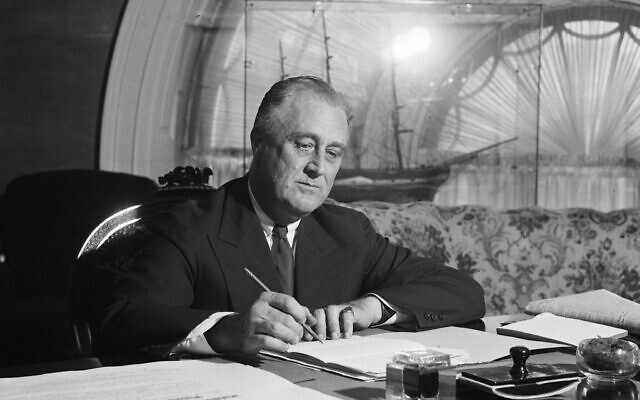

The US, too, opted for inaction. “Bureaucratic buck-passing and paper shuffling,” as Freedland describes it, characterised the response of US diplomats in Switzerland after they obtained the report. Pressing appeals for bombing, handed by Jewish group contacts within the US, met a wall of resistance. Roosevelt himself determined that the US might find yourself “accused of collaborating on this horrible enterprise” had been its bombs to finish up killing Jews.

US President Franklin D. Roosevelt (Courtesy of PerlePress Productions)

Reactions to the report in London and Washington additionally revealed that, regardless of the horrors it contained, previous prejudices remained unshaken. The US Military journal, Yank, as an illustration, declined to make use of materials from it in a characteristic on Nazi conflict crimes, requesting as an alternative “a much less Jewish account.” In the meantime, within the UK International Workplace, civil servants bemoaned the “normal Jewish exaggeration” and the period of time expended on “these wailing Jews.”

However, alongside these responses, there was additionally a swirl of disbelief surrounding the report’s revelations: one which affected not solely the Allies however even some Jews themselves. It was maybe finest captured by the phrases of the French-Jewish thinker Raymond Aron: “I knew, however I didn’t consider it. And since I didn’t consider it, I didn’t know.”

I believe this goes to one thing very profound about human nature and our restricted skill to listen to horrible information

“I believe this goes to one thing very profound about human nature and our restricted skill to listen to horrible information,” says Freedland. “We are able to have the knowledge with out it ever turning into one thing we absolutely, really consider.”

Information, he says, must be mixed with perception earlier than they change into information, which is itself the spur to motion. For all his insights into how the Nazis had been utilizing deception to perpetrate their horrible crimes, the teenage Vrba hadn’t reckoned on such sentiments.

An ‘extremely witness’ bearing uncomfortable testimony

After the conflict, Vrba returned to his native Czechoslovakia, later dwelling in Israel and Britain earlier than lastly settling in Canada. He married twice — the writer interviewed first and second wives Gerta and Robin for this e-book — and had two daughters, Helena and Zuza. Vrba additionally had a profitable tutorial profession as a biochemist.

He additionally turned what Freedland phrases an “ultra-witness”: writing his personal memoirs; giving professional testimony in a number of instances involving conflict criminals and Holocaust deniers; and sharing his maybe unparalleled insights into the working of Auschwitz with the foremost chroniclers of the Shoah, together with the historian Martin Gilbert and documentary-maker Claude Lanzmann.

Creator of ‘The Escape Artist’ Jonathan Freedland. (Philippa Gedge)

Vrba’s story, nevertheless, by no means obtained the broader recognition or standing afforded to different rescuers, like Oskar Schindler, or fellow survivors equivalent to Elie Wiesel or Primo Levi.

“I believe it’s as a result of he was a clumsy, uncomfortable witness who spoke awkward, uncomfortable truths,” says Freedland. “He pointed an accusing finger, partly at Whitehall and Washington… [but], far more sensitively, at a restricted variety of people within the Jewish management, particularly in Budapest. That was not a narrative many individuals needed to listen to in Rudolf Vrba’s lifetime.”

He was a clumsy, uncomfortable witness who spoke awkward, uncomfortable truths

However, as Freedland says, reactions to Vrba’s story replicate a wider concern with how Holocaust survivors have typically been handled.

“I believe we — the media, educators, and others — have put, and proceed to place, a really unfair strain on Holocaust survivors to serve up a form of comforting, therapeutic knowledge and to make us really feel higher for having spoken to them,” he says.

This strain, he continues, denies survivors the chance to specific “a spread of responses to the gravest doable trauma, together with anger.” Vrba’s response, in fact, was anger — an anger which few readers of the e-book will conclude was unjustified.

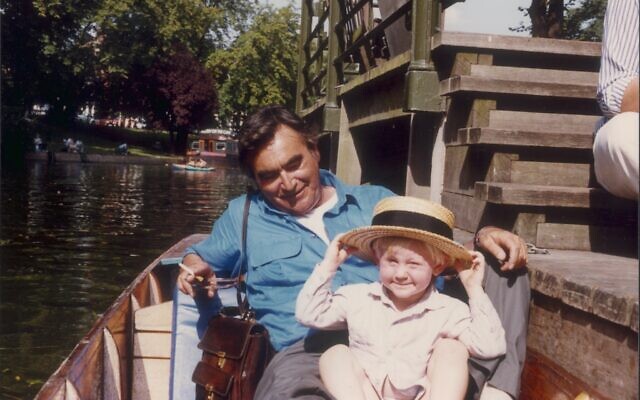

Rudolf Vrba and grandson Jan in Cambridge within the Nineties. (Courtesy of Robin Vrba)

Freedland believes that Vrba, who he phrases a “hero for our occasions,” shouldn’t merely be judged by his previous heroism but additionally by his present relevance.

In a post-truth age — the place so many lies proliferate by social media, propaganda and lively disinformation — the story of this teenage boy from the Nineteen Forties serves as a reminder “that the distinction between fact and lies could be the distinction between life and loss of life,” he says. “Rudolf Vrba couldn’t be a extra modern determine and, in some methods, an urgently inspiring one.”

[ad_2]

Source link